Parkland panel subpoenas deputy who first responded to massacre

TALLAHASSEE (NSF) - Scot Peterson, the Broward County school-resource officer who was responsible for protecting students at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School, has been subpoenaed to appear next month before a state commission investigating the Valentine’s Day massacre that left 14 students and three faculty members dead in one of the nation’s worst mass school shootings.

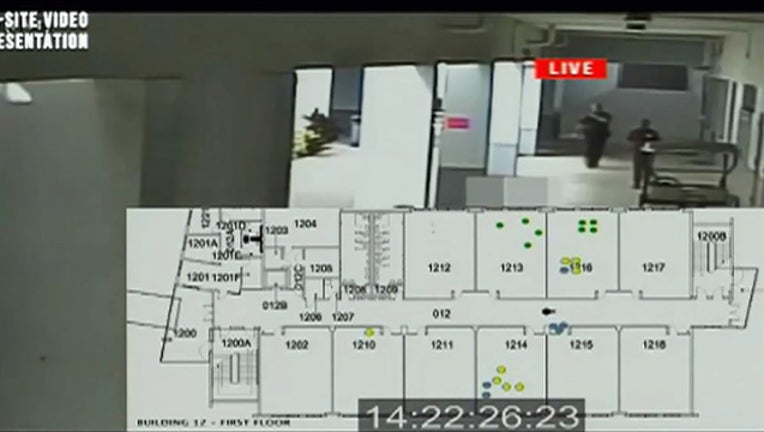

The Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School Public Safety Commission spent hours Wednesday debating the role of school resource officers before concluding the meeting with a chilling recreation of the Feb. 14 shooting that included video of Peterson failing to enter the “1200 building” as a deadly hail of bullets rained down on students and faculty.

The video was overlaid with animation of the massacre that depicted alleged shooter Nicholas Cruz, a former Stoneman Douglas student, with a black dot, while students and faculty were portrayed by green dots that turned gray after they were shot and killed. Cruz initially confessed to the killings but has pleaded not guilty to 17 charges of murder.

The video and the graphic representation, accompanied by audio recordings of law enforcement’s response, elicited disgust, anger and dismay from the panel, which includes the fathers of two slain Stoneman Douglas students.

During the presentation by Broward County homicide detective Zach Scott, Max Schachter, whose 14-year-old son Alex was among the students who died, repeatedly referred to Cruz as “the monster,” refusing to call the alleged killer by his name.

The video includes footage of Peterson, the only armed person on the 45-acre campus, huddled outside the freshman building 69 feet from where Cruz could be heard mowing down students and faculty.

At one point, Peterson advised other law-enforcement officers to stay away from the building where the shots were being fired and to block off the road leading to the Broward County school.

Peterson, who retired shortly after the mass shooting, never entered the building, something that tore at Schachter and Pinellas County Sheriff Bob Gualtieri, the commission’s chairman.

Gualtieri noted that Cruz reloaded the AR-15 rifle five times throughout the three-story killing spree, before blending in with the students who fled the building.

It’s possible Peterson could have prevented some of the deaths, Gualtieri said. Shots could be heard in the background on calls Peterson made while reporting the incident, he said.

“As opposed to going in, he retreated and ran,” the sheriff said. “We’ll see him leave the door, after saying there were shots fired and hearing shots.”

Peterson waited before reporting what he heard, and other law-enforcement officials were delayed in responding to the incident because of issues with different radio systems used by Broward County and the Parkland and neighboring Coral Springs municipalities, according to testimony provided to the commission.

Peterson may have cost lives “because he didn’t notify” fellow sheriff’s deputies “when he first became aware of the problem,” Gualtieri said.

Advising others to “lock down the roads” and “about staying back” is “totally contrary to all law enforcement policy,” Gualtieri said.

Peterson’s actions caused chaos, and confusion continued to mount during Cruz’s four-minute attack, Gualtieri indicated.

“This whole time, look at the video, see where Peterson is. He’s standing outside the building, hiding in the corner,” the sheriff said.

Schachter struggled to maintain his composure throughout the two-hour presentation Wednesday afternoon, repeatedly asking questions of Scott in preparation for Peterson’s scheduled appearance before the commission on Oct. 10.

“I just want to have as much information, when he comes and stands here, before that happens,” Schachter said. “You teach all of your officers to go in, go towards the bullets, right?”

“Active shooter” laws require law enforcement responders to “move toward” the perpetrator, even if they have to walk over injured or dying individuals, Scott said.

“You step past them. Because every shot you hear is another potential victim,” the detective said.

The presentation revealed “a lot of mistakes,” Schachter said.

“A lot of humans that did not operate. All were cowards. Hopefully if you had some good guys with a gun, they would have done something,” he said. “That’s the reason I will contend we need a fail-safe mechanism and that’s the reason why we need to harden these buildings. In an emergency situation, you never know how they’re going to react. That’s why you need a fail-safe. We need to harden these buildings.”

When asked whether Peterson would appear next month, Gualtieri said he expected the former deputy to follow the law.

“If he felt that it was all right to go sit down with the “Today” show, and he felt it was all right to go interview with the Washington Post, then he should stand here and answer your questions,” the sheriff said. “He has no legal basis not to appear. So I would expect he’ll follow the subpoena.”

The Washington Post in June published a lengthy story in which Peterson recounted his actions on the day of the shooting and defended himself against criticism.

“How can they keep saying I did nothing?” the Post story quoted him as saying to his girlfriend. “I’m getting on the radio to call in the shooting. I’m locking down the school. I’m clearing kids out of the courtyard. They have the video and the call logs. The evidence is sitting right there.”

Earlier Wednesday, the state commission spent hours debating recommendations about school resource officers --- who are sheriff’s deputies or who work for police departments affiliated with school districts --- and the school “guardian” program created in response to the Stoneman Douglas shooting. The controversial “guardian” program allows specially trained school personnel to carry guns to schools. Twenty-five of the state’s 67 counties have authorized the school guardian program.

The Legislature this spring steered $400 million to schools to address school safety, including a $97 million increase to hire more school resource officers and $67 million for the “guardian” initiative. All but $500,000 of the funding for the guardian program, however, was a one-time allocation.

The law also required each school to have at least one “school safety officer,” who could be a law enforcement officer or a “guardian.”

But on Wednesday, the commission settled on a recommendation that would require at least one school resource officer at each middle school and high school, and at least one guardian at each elementary school.

Gualtieri discouraged the panel from requiring a resource officer in every school. He said the Legislature would not support the $400 million price tag for the requirement.

But Desmond Blackburn, a former Brevard County superintendent of schools, disagreed with the recommendation, approved by a 9-5 vote. The total for the resource officers amounts to less than half of one percent of the state’s budget, Blackburn said.

“We have ports. We have nuclear facilities. We have courthouses. We have the Dolphins’ next football game. … All more adequately protected than our schools,” he said. “Every school, every campus, should have a police officer on it.”