Gas Plant District in St. Pete: One of the oldest Black neighborhoods razed for baseball

St. Pete mayor discusses Gas Plant District

St. Petersburg Mayor Ken Welch grew up in Gas Plant. He has fond memories of learning the value of hard work and being held accountable as a child. It was a close-knit community that was promised an economic return when the city voted to demolish the neighborhood to build a baseball stadium. Those promises have yet to be fulfilled, but, he said, it's not too late.

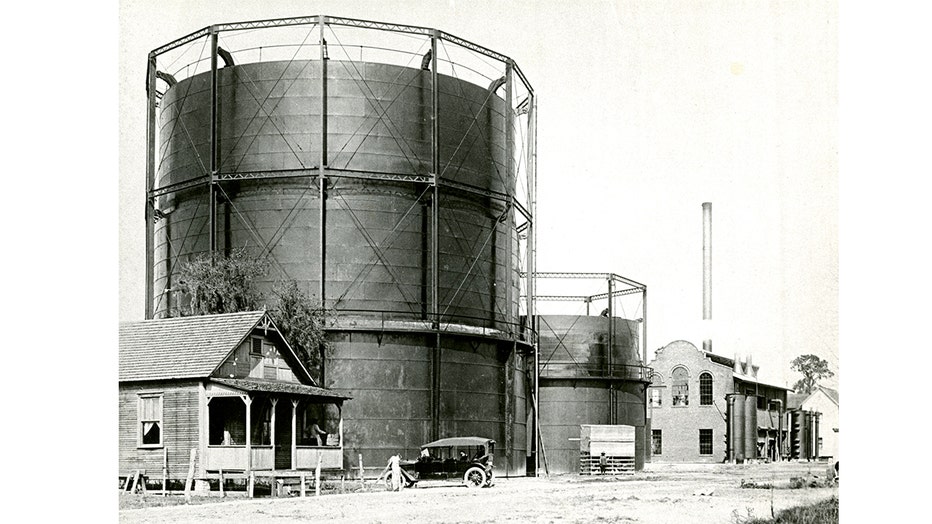

ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. - In the heart of downtown St. Petersburg, two gas cylinders once stood, casting twin shadows over a bustling neighborhood.

There were hundreds of African Americans who called Gas Plant their home – before Tropicana Field took its place. The tightly knit community was around for nearly a century.

In the 1980s, as city leaders began taking steps to redevelop the Gas Plant neighborhood, their attention turned to building a stadium to lure an MLB team to the area.

It was during a time when St. Pete's economy was stagnant. With America's greatest pastime in the city's roots, officials decided to move forward with making Gas Plant the site of a future baseball stadium.

That meant families had to leave behind their homes. Many businesses didn't survive the relocation.

While the Black residents were compensated by the city to relocate, they were also promised other forms of economic return for their sacrifice – but never received it.

Aerial view of the Gas Plant District with the iconic cylinder towers pictured. (Provided by the City of St. Petersburg)

Today, the remaining Gas Plant residents are scattered throughout the city and country. While they lost their community, those memories of weekly crab boils and barbecues, children building their own wooden scooters to visit friends, and plucking fresh fruit from mango or guava trees, are ones that have stayed with them.

Their story, while complex, isn't just about baseball and broken promises. Many moving parts throughout history ultimately led up to not one, not two, but three African American communities uprooted in downtown St. Pete.

Working on the Railroad

There was a period of time when only one African American family lived in present-day St. Pete. In 1868, John Donaldson and Anna Germain became the first Black settlers in the area.

According to the St. Petersburg Museum of History, Donaldson was previously enslaved in Alabama. He arrived in lower Pinellas County after the Civil War ended to work for Louis Bell, Jr. That's where he met Anna Germain, Bell's housekeeper.

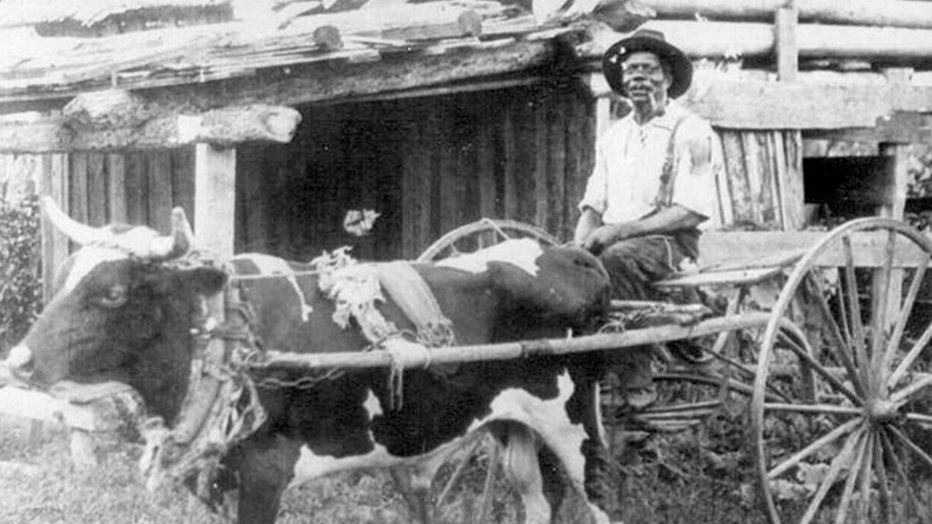

John Donaldson using an oxtail-drawn wagon. (Provided by the St. Petersburg Museum of History)

Donaldson and Germain were later married and had 11 children. The couple purchased a 40-acre farm near Salt Lake, where present-day Lake Maggiore is located.

Donaldson became the first Black man to own property in the area.

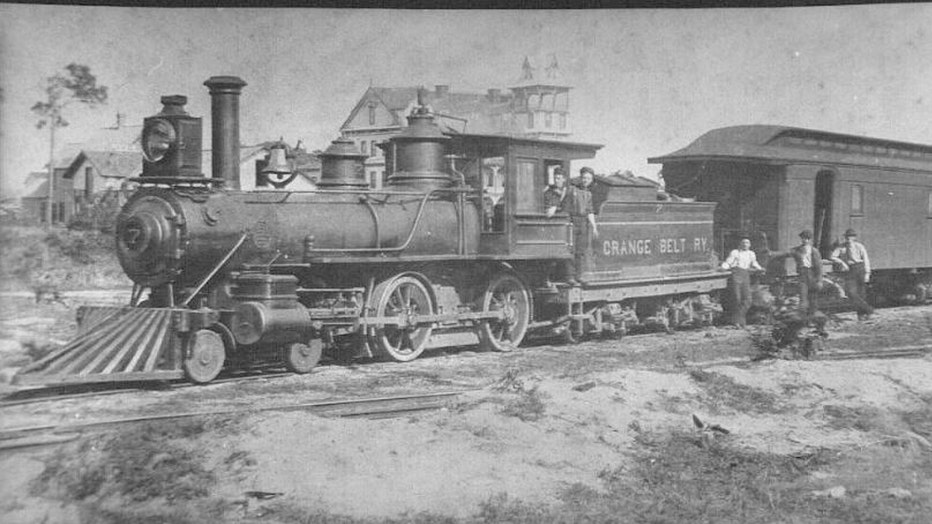

Then, the Orange Belt Railway came through town. The railway extended from Sanford to Tampa Bay, allowing easier access to lower Pinellas and sparking economic growth for the region in the years that followed.

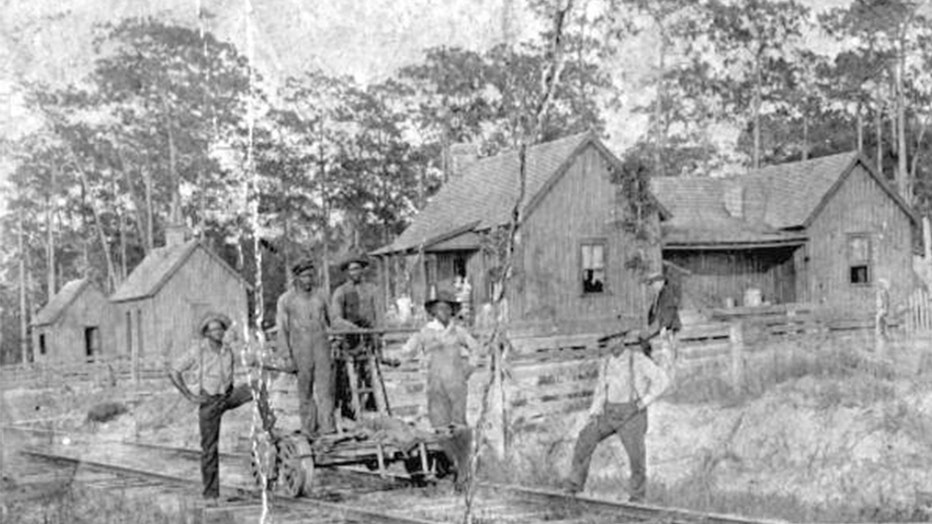

Its construction brought hundreds of Black workers to the area, explained Gwendolyn Reese, the president of the African American Heritage Association of St. Pete.

African-American workers at the site of Orange Belt Railway. (Credit: State of Florida Archives)

"There was a need for workers to complete the construction of the railway," she told FOX 13. "[The city] wanted to attract tourists, and they couldn't do that unless there was a way for tourists to get here – and so the railway was that way."

The railroad was completed by 1889, and many Black workers chose to stay.

Engine No. 7 was part of the Orange Belt Railroad. It traveled to St. Pete as early as 1890 with passengers who were also Detroit Hotel guests. (Provided by the St. Petersburg Museum of History) ( )

READ: From the Railroad Era to the inverted pyramid, St. Pete's piers took on many forms since the 1800s

"When I think about it and talk about it, African Americans have been an integral part of the building of this city," Reese said, "because they were the ones to actually complete the railway, without which St Pete would not be what it is today."

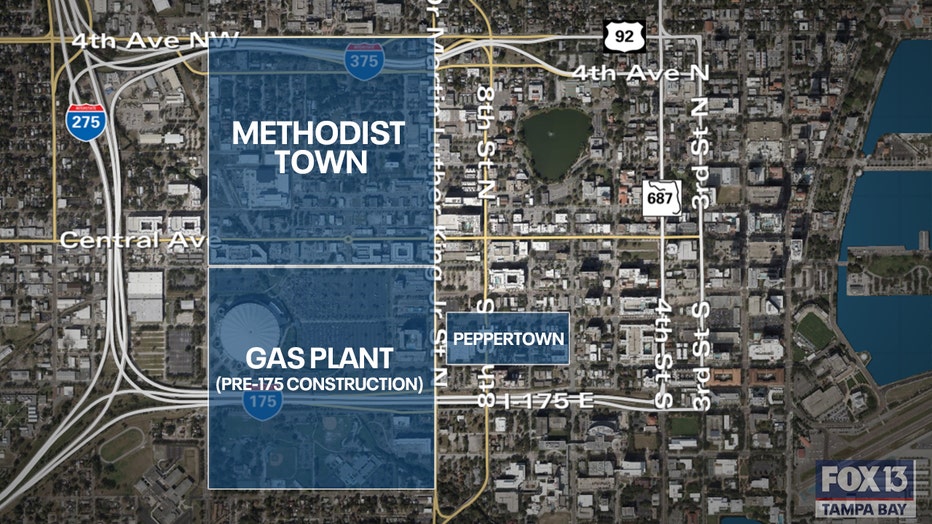

Early on, there were a handful of neighborhoods where African Americans resided. The Black rail workers who chose to stay, mainly settled in Peppertown. It was east of 9th Street South – which is now Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard – between 3rd and 4th avenues.

In 1894, Methodist Town was founded and grew north of the railroad. It was the only neighborhood north of Central Avenue, with its loose northern borders where Interstate 375 is today.

Cooper's Quarters was located in the northeast corner of the Tropicana Field site, along 9th Street South and south of 1st Avenue. It grew along with other micro-neighborhoods to become Gas Plant, Reese explained.

These were the original settlements for African Americans in St. Pete.

All three neighborhoods no longer exist.

Two natural gas cylinders in the Gas Plant neighborhood. They were later demolished to make way for a multi-purpose stadium. (Provided by the City of St. Pete)

What happened to Peppertown and Methodist Town?

In "Where Have All the Mangoes Gone," a 2019 master's thesis written by Sarah-Jane L. Vatelot, she cited "security maps" used by the Home Owner's Loan Corporation. It was drafted in the 1930s.

Among the considerations that qualified a neighborhood as "hazardous" or declining" was the proximity to or demarcation of a "negro section." One decision which resulted from the compiling of these security maps was the city's 1935 "Proposed Negro Segregation Project"…in which a legal description is provided for the relocation of African Americans who were deemed to be located within too close of a proximity to Downtown.

In an effort to clean up Downtown's image, to be more appealing to tourists, the residents of Methodist Town, Peppertown and the Gas Plant would need to be relocated.

Peppertown was deemed as "blighted." Jordan Park – named after Elder Jordan, who donated the South St. Pete land to the city – was built between 1939 and 1941 as the city moved toward redeveloping the three Black neighborhoods. In 1940, voters approved the complex for Black residents as an affordable alternative for the three neighborhoods.

The loose boundaries for the original three Black neighborhoods of St. Pete are shown for Methodist Town, Gas Plant and Peppertown (FOX 13)

It is the oldest federal public housing project in Florida and the city's first Black public housing complex. Most of the Peppertown residents were relocated there, and the neighborhood was gone by the 1940s.

Methodist Town was established in 1894, built around Bethel AME Church on 3rd Avenue North. Its boundaries were roughly 1st Avenue North, 5th Avenue North (I-375), 9th Street North, and 16th Street North.

Chester James, a resident who was named the honorary mayor by city council officials, advocated on behalf of Methodist Town.

The security maps, according to Vatelot's research, noted Methodist Town had "dilapidated repair conditions of the majority of properties," and blamed tenants. However, James lobbied for the city to turn their attention to the landlords, saying they were the ones neglecting those properties. He also tried to lobby city leaders to improve unpaved roads in the community.

In the early 1970s, St. Pete city leaders marked Methodist Town and Gas Plant as priorities for redevelopment. In 1974, James worked with the city on those efforts, believing the improvements he was advocating for would eventually occur. Instead, it led to the relocation of 377 families.

The Historic Bethel AME Church remains the first and oldest Black church in St. Petersburg.

According to Vatelot's thesis, Jon Wilson, a former reporter for the St. Petersburg Times, was at a city council meeting where James "waved his cane" at city council members, "who, it can be said, had used him to achieve their ends."

James' home was demolished.

The city renamed the area Jamestown.

According to the New York Academy of Medicine, urban renewal impacted "thousands of communities in hundreds of cities," just like Jamestown.

"Urban renewal programs fell disproportionately on African American communities, leading to the slogan ‘Urban renewal is Negro removal.’ The short-term consequences were dire, including loss of money, loss of social organization and psychological trauma."

Another community, The Deuces, along 22nd Street South, roughly between 1st and 18th avenues, was impacted over the years by the highway construction. It was once a busy main street for the African American population in the area.

From 2021: St. Pete leaders sign off on Deuces development

St. Petersburg city leaders took another step this week toward helping revitalize a historically Black neighborhood, approving a lease for city-owned land to build a major mixed-use development in the Deuces corridor.

There are some notable buildings still standing. Elder Jordan helped build a 12,000-square-foot entertainment facility in The Deuces.

It opened in 1931 as Jordan Dance Hall and later became known as the Manhattan Casino. Legendary performers like Louis Armstrong, Ray Charles, and James Brown performed there.

Today, the Historic Manhattan Casino is an active event venue and food hall.

Life as a Gas Plant Resident

An excerpt from "St. Petersburg's Historic African American Neighbors" – written by Wilson and Rosalie Peck, who were born in St. Pete and raised during the Jim Crow era – reads in part:

During the first six decades of the twentieth century, African Americans in St. Pete were forced to create their own insular society, where going to school, finding a home, eating out at restaurants, and seeking medical treatment was conducted separately from white residents. Blacks were treated so unfairly that even African American police officers did not have the right to arrest whites until 1965. Of course, this was not exclusive to St. Pete, but prevalent in much of the Deep South, where Jim Crow was the way of life.

An aerial view of Gas Plant, where the two gas towers are visible. This is before the interstates were built.

In St. Pete, a building boom occurred between 1921 and 1926, and Black workers were recruited from Georgia and Alabama. The population tripled from 2,444 in 1920 to 7,416 in 1930, according to a 2021 Structural Racism Study by the city of St. Pete. During this time, a large percentage of St. Pete's earliest settlers were "rabidly pro-Confederate."

A 1931 city charter in St. Pete made it forbidden for Blacks to live or operate a business in a white neighborhood and banned white people from doing the same in Black neighborhoods. Five years later, the city council passed a resolution that forced African Americans to live west of 17th Street and north of 15th Avenue South.

LINK: Read the entire 2021 Structural Racism Study here

Other restrictions were placed. Black people couldn't use public restrooms or sit on St. Pete's iconic green beaches. They couldn't try on clothes in stores along Central Avenue. In 1943, the city purchased Campbell Park to use as a park for African-Americans during the Jim Crow era.

While they lived in the same area for convenience, it was also for safety. With the barriers created for them, the African-American communities had to make it work. For children and others residing in places like Gas Plant, they didn't see the boundaries. They didn't see the red lines.

They saw a home.

Photo of a home in the Gas Plant neighborhood (Provided by City of St. Pete)

When you speak to Gas Plant residents today, they collectively tell a similar story, recalling a general, warm sense of community.

"Everybody has wonderful memories," Reese explained, adding that she interviewed dozens of fellow Gas Plant residents for a documentary. "We all sort of describe our lives very similarly. We had lots of fun. We had good neighbors. We felt safe. We didn't have to lock our doors. We were talking about how often we got together in backyards for some crab boils and fish fries."

They talked about the avocado, guava, and mango trees. She remembers the cherry bushes outside Dr. James and Fannie Ayer Ponder's home on Fifth Avenue South, an area that was once known as Sugar Hill, a sub-neighborhood of Gas Plant.

For Reese, she remembered her first school, the private McCray's school. Not everyone went to that school because it required families to pay.

"I want to tell you that all of us who attended that school, we were reading at four and five years old," she explained. "That's the quality of education."

There were apartments, bungalows, and modest, two-story homes, Reese described. It didn't matter what occupation a Gas Plant resident held – whether it be a doctor or sanitation worker – they all lived in the same community. It allowed children living next door to certain professionals to learn from them.

A two-story home in the Gas Plant community. (Provided by City of St. Pete)

"They were living role models that you sat and talked with, that you knew, that you did errands for who were invested in your success and in your education," Reese explained. "So, out of this Jim Crow racist policy grew very strong neighborhoods."

READ: 1920 Ocoee Massacre: Largest U.S. incident of voting-day violence occurred in Florida

Children got creative with toys. They even built their own scooters, piecing together wood with wheels from roller skates. Soda pop tops were used for decorating.

The Harlem Theater and Citizen's Lunch Counter were just a few businesses that were thriving. Davis Academy, the first African American elementary school in St. Pete, opened here. St. Pete's first African American physician, Dr. James Ponder called Gas Plant his home.

About six generations of Gas Plant residents lived in the district.

"Don't get me wrong," she said, "redlining was wrong. It was racist. But out of those red-line neighborhoods, like the Gas Plant neighborhood, we had these thriving, supportive, loving, safe, very rich cultures and experiences."

The Pursuit of Baseball

The story of Gas Plant's disappearance began with the intention to redevelop it, city officials have said over the years. Records show council members in the 1970s established it for revitalization and designated it as an area of "slum," under Florida Statutes.

LINK: What's the legal definition of slum and blighted? Read the Florida Constitution here

"Fortunately, I never lived in any of those structures," Reese recalled. "The apartment building my parents lived in until I was in fifth grade and…their first home were not dilapidated. It had indoor plumbing, it had all of that. It was an apartment, but it was not a slum. But there were slum areas in the Gas Plant neighborhood. But the Gas Plant neighborhood itself in its entirety was not a slum."

Naturally, there was some hesitancy. Just before revitalization discussions began, the construction of Interstate 275 and Interstate I-175 dislocated many African American households and isolated Gas Plant from surrounding neighborhoods. Its southern boundary was once as far as 7th Avenue South, connecting it to Campbell Park.

This map shows Gas Plant's loose boundaries and where the southern border was before and after the construction of I-175.

According to the Gas Plant Redevelopment Plan at the time, 81% of the structures were rated as "deteriorated or dilapidated." The original plan was to create commercial spaces and an industrial park in Gas Plant that would lead to 680 jobs, plus construction jobs over the following years. The city also planned to provide new homes for over a thousand people.

A referendum was held and the majority of St. Pete residents voted in favor.

____________________________________________________________________________

What was promised to Gas Plant residents?

"There were 27 businesses and 859 total employed persons in the Gas Plant Area. According to the Gas Plant Redevelopment Plan, the City was to acquire and demolish substandard structures and accessory buildings, rehabilitate suitable dwelling units and assist property owners to secure financial assistance if necessary, relocate families, individuals, and commercial establishments in acquired structures in accordance with the Uniform Relocation Assistance and Real Property Acquisition Policies Act of 1970, and create substantial public improvements to encourage new development, primarily commercial and residential uses east of 11th Street South and industrial uses west of 11th Street South.

However, those promises went unfulfilled."

- 2022 Historic Gas Plant Site Request for Proposal

____________________________________________________________________________

In 1983, the city officially modified the original plan to include building a multipurpose stadium. Rick Mussett, the former Senior City Development Administrator and Planning Director for the city for nearly 35 years, said the redevelopment efforts coincided with discussions of attracting an MLB team.

"We had this development…that was going to be vacant, and it was very much near the interstate, which is really good for people coming from Tampa or Manatee County, the regional area," he explained. "So, it was deemed a good opportunity. The site just popped up because that was already available."

He also noted the city's baseball history, which dates back to 1914, was another reason. Plus, city officials believed it would be an opportunity to attract more tourists and businesses to the downtown area.

MORE: St. Pete and baseball: A relationship that spans over a century

"When they changed their minds to do a baseball stadium," Reese explained. "There was no referendum. They just changed from, 'We're not building this, we're building that.' I'm very comfortable saying they lied. A lot of African Americans did not want that. They did not want to move out of the Gas Plant area. But there was some who felt that it would be progress for us based on what they said they were going to do."

New book captures connection between baseball and St. Pete

Rick Vaughn has a lifetime of baseball memories, 30 of which he has spent in Tampa Bay. It led him to author a book titled "100 years of Baseball on St. Petersburg's Waterfront."

One of the Gas Plant residents who believed in those was the late David Welch, who was city councilor at the time and voted in favor of building the stadium. He previously stated he didn't believe a referendum on building a stadium would've passed, if there was one.

"That was a slum area," Welch told the St. Petersburg Times in 2007. "They had the jail on one side, the gas plant on the other. Those places were undesirable."

At first, he opposed the plan but believed that, ultimately, the promise of jobs, opportunities for minority business development, and a chance for Black businesses to thrive in the new economic environment would occur.

His son, Kenneth Welch, will later become the mayor of St. Petersburg as the Tropicana Field site enters another redevelopment phase.

Ken Welch elected mayor of St. Petersburg

St. Petersburg elected its first Black mayor. Ken Welch won with more than 60 percent of the 65,000 votes.

Nine churches and 500 households were relocated, while 285 buildings were demolished. The Gas Plant project led to 40 businesses moving or closing.

"The Gas Plant redevelopment was the seventh mass displacement, over a dozen years, that relocated 2,100 Black families, businesses, and institutions from their homes in the city’s segregation-era Black neighborhoods," the 2021 study read in part.

Residents were offered market value for their property, Mayor Welch told FOX 13, adding that his father had a hand in helping Gas Plant residents transition. There were some who worked out better deals.

"That area was a low economic area," the late Clarence Welch, David's brother and Ken's uncle, told the Times in 2007. "A lot of those people did not have the expertise of negotiating."

Reese said she hears several stories from Gas Plant residents who were compensated and purchased or rented property elsewhere, but not all had happy endings. There were struggles. For some, the money received from the city was not enough to buy another piece of property, so they ended up with mortgages.

She described the story of one former resident Carlos, who was interviewed for her documentary.

"He remembers leaving the Gas Plant neighborhood, leaving the house they had, buying another house because they were compensated but not a house they could afford," she explained. "Losing that house because they could not afford the payments living. He remembers being homeless for a while."

The pursuit of an MLB team required more. The city later demolished the Laurel Park Housing complex in 1990 to make way for more parking spaces, Lots 1-4, specifically. The entire Tropicana Field site was now 86 acres – 20 from Laurel Park and 66 from Gas Plant.

The only remaining structures from that era are the former Graham Rogall housing project, which is now a privately-owned apartment building, and a U-Haul business at 1st Avenue South and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Street.

During the construction of the Florida Suncoast Dome, contamination of the soil and pollution in Booker Creek were discovered. Mussett said it was what remained from the natural gas plant that once was there. The stadium finally opened in 1990.

FOX 13 Archives: Early years of the St. Pete dome construction

In this report on January 5, 1987, Pulse 13's Marianne Pasha describes the status of the dome construction, which was put on a fast-track schedule with the goal of completing it in two years. At this point, there were unresolved lawsuits and questions surrounding the stadium's design.

In 1988, St. Pete was close to welcoming the Chicago White Sox as the team faced its own stadium saga, but they ultimately stayed in Illinois.

The 1993 MLB expansion left St. Pete out, but it was two years later when the league finally rewarded the city with a team.

The Tampa Bay Devil Rays played their first home opener in 1998.

Teaching the Next Generation

When there isn't a home game, Tropicana Field sits still and quiet, casting a wide, uneven shadow in the hot Florida sun over its empty parking lots.

In December 2021, former Gas Plant and Lauren Park residents gathered across the street, sharing stories in Lot 4. They talked about everything that came before the Trop.

"I wasn't interested in baseball then," Reese said, "and I'm not interested in baseball now."

Black History Museum needed in St. Pete, mayor says

In February 2022, St. Petersburg's first Black mayor, Ken Welch kicked off Black History Month by raising the African American history flag over City Hall. Community leaders say they want a new museum to preserve that history.

The neighborhood reunion was an opportunity to celebrate the past. It reconnected former residents who haven't seen each other in years.

"Her name is Kimberly," Reese began, describing a former resident who attended the reunion, "and she heard somebody calling her name, ‘Kimberly! Kimberly!’ And so she turned around. She didn't recognize her. And the woman said, 'Don't you know who I am?' Well, the woman's name was Kim, too. They were best friends in elementary school, and they hadn't seen each other for over 40 years. That's what reunions do."

There were about 300 in attendance. Among them were the owners of a food truck, Betterway Catering. Their grandfather once owned a Gas Plant business called Betterway Cleaners, and wanted to continue that legacy.

They were slinging out BBQ to residents and the generations that came after. Reese said they have the best banana pudding.

"It was just a joyous time and that's what it was meant to be," Reese offered. "I did not allow anyone who spoke to talk about the Tropicana Field redevelopment. It was not about that. It was a celebration."

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, the African American Heritage Associate gave personal trolley tours of the Heritage Trail. Now, it's gone digital with a self-guided option. The interactive guide can be used on phones, tablets, or computers.

Anyone can walk the Heritage Trail themselves or watch all the videos and interviews at home. The free interactive digital guide can be found here.

"I cannot accept our stories being excluded from the story of St. Petersburg," Reese said. "I cannot accept that. So, I will change that by telling our stories, by sharing our stories everywhere."

It's narrated in part by Reese, along with Jon Wilson, the former Times reporter who witnessed Chester James scolding city council when Methodist Town residents were forced to move. It tells the story of St. Pete's Black history, which includes the Gas Plant neighborhood.

"Everybody's story is important. Everybody's story matters," Reese offered. "You know, there's the Serenity Prayer that says, ‘To accept the things that cannot change.’ Angela Davis, [the activist], says, 'I'm no longer willing to accept the things I cannot change. I'm going to change the things I cannot accept.'"

"I embrace that," she added, "and so I'm going to change what I cannot accept."

The historical information in this article was provided by Gwendolyn Reese, president of the African-American Heritage Association of St. Petersburg; ‘Where Have All the Mangoes Gone: Reactivating the Tropicana Field Site on the Threshold of St. Petersburg’s History, Culture, and Memory,' a master's thesis project by Sarah-Jane L. Vatelot' the Structural Racism Study conducted by the City of St. Petersburg; and the St. Petersburg Museum of History.