Heart tissue that traveled to space may benefit patients on Earth

Researchers study heart tissue that traveled in space

It?s now back on Earth, and right here in the Tampa Bay Area. Researchers from Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore are working with NASA to study the effects space has on heart tissue.

ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. - Human heart tissue took a trip to space and it was all for science.

It’s now back on Earth, and right here in the Tampa Bay Area. Researchers from Johns Hopkins Medicine in Baltimore are working with NASA to study the effects space has on heart tissue.

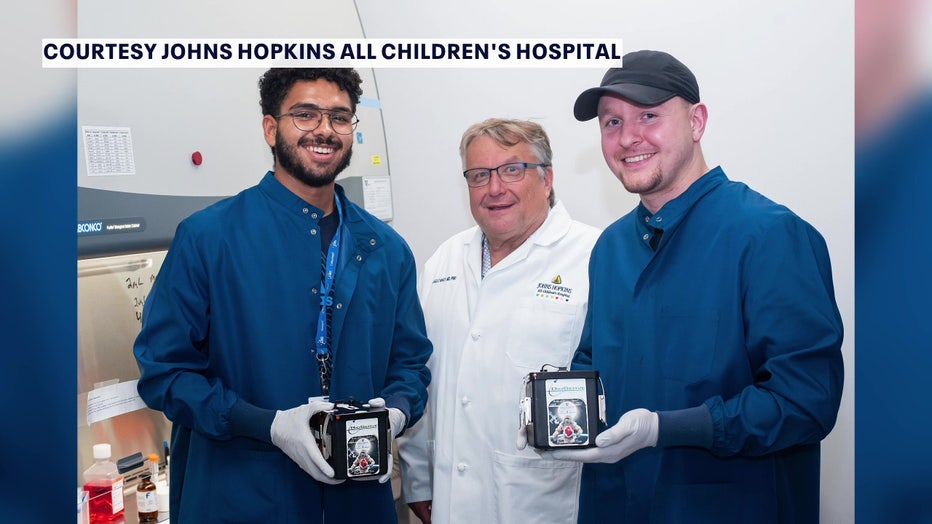

Devin Mair engineered the human heart tissue from an anonymous human skin sample. After more than 40 days of prepping the samples, Mair said the samples spent 30 days at the International Space Station aboard SpaceX CRS-27. They splashed down Sunday.

It's part of Dr. Deok-Ho Kim's study. Dr. Kim is a professor of biomedical engineering at the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. The first spaceflight experiment was in 2020, Mair said. They determined from those impacts that they needed to do it again and screen drug treatments to prevent the negative effects they saw during the first mission.

"We're trying to process them very, very quickly to get all of our live cell data," Mair said. "We're then going to preserve them and do some further studies on them over the next couple of months."

Researchers with heart tissue that went into space courtesy of Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital.

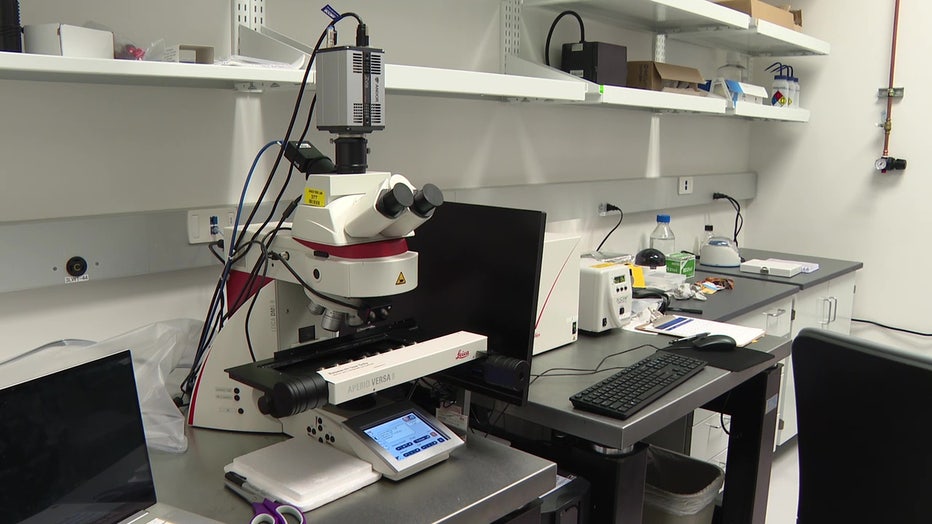

Mair said flying the samples back to Baltimore was too risky, and the Kennedy Space Center isn't equipped with what they need, but Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital in St. Pete had the ability.

READ: Bill banning social media sites on school devices awaits DeSantis’ signature

"Kennedy Space Center is fantastic for a lot of things, but life sciences, they're not as equipped as the research center here in St. Petersburg. So, we decided to collaborate with the group here to try to get all of the additional data that we needed," Mair said.

Microscopes used at Johns Hopkins All Children's Hospital in St. Pete

"They really have just world-class microscopes, plate readers, etc., that Kennedy Space Center just does not have," he said.

Mair drove the samples from the Kennedy Space Center to All Children’s.

"Any travel with these is obviously terrifying. Just casually driving down the street with engineered heart tissues from the International Space Station is probably one of the scariest moments of my life," Mair said.

Dr. Laszlo Nagy, the co-director of the Institute for Fundamental Biomedical Research at All Children's, is helping the team on this end.

MORE: LifeLink Foundation honors organ donors

"You can ask the Baltimore colleagues," Dr. Nagy said. "They are all amazed about the quality of the infrastructure and the resources and the quality of the people. You know, I think it's very important to emphasize that buildings don't do science. People do," he said.

"I think it's very important that this high level of infrastructure is available, and I think it's equally important that it's tied, very sort of organically, to a world-famous university such as Johns Hopkins," Nagy said. "I think it's just a nice embodiment of the collaborative effort which can, can result in significant findings," he said.

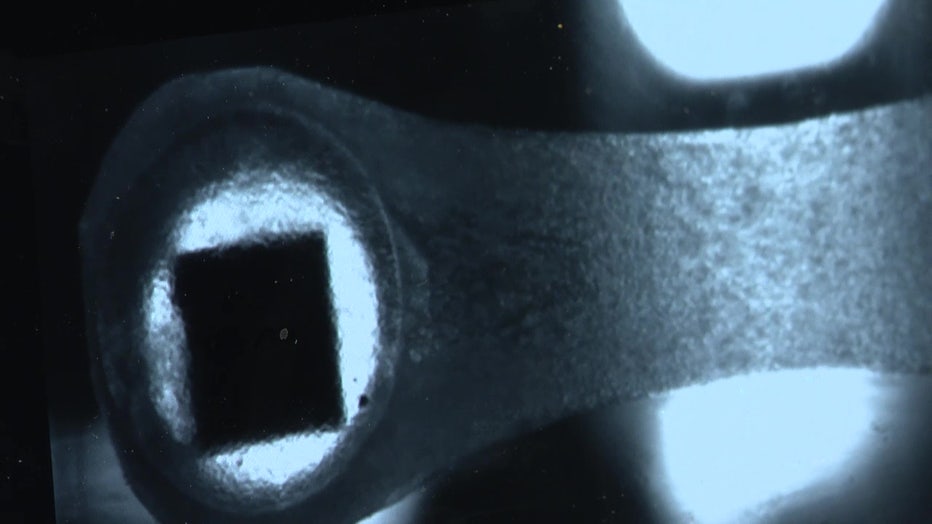

Microscopic view of heart tissue that went into space.

Mair said they've found signs of mitochondrial dysfunction and possible links to cardiac dysfunction. He said the study also impacts those of us here on Earth.

"Spaceflight has a lot of similar effects on the human heart as aging does. So, we're hoping that what we found can also have terrestrial impacts for aging heart disease," Mair said.

The National Institutes of Health and NASA funded the study. These samples were the last of that funding, but Mair said they plan to apply for more. He plans to defend his thesis on this work next month.