From Gas Plant resident to St. Pete mayor, Ken Welch's life comes full circle

St. Pete mayor discusses Gas Plant District

St. Petersburg Mayor Ken Welch grew up in Gas Plant. He has fond memories of learning the value of hard work and being held accountable as a child. It was a close-knit community that was promised an economic return when the city voted to demolish the neighborhood to build a baseball stadium. Those promises have yet to be fulfilled, but, he said, it's not too late.

ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. - Walking through the empty city council chambers, wearing blue denim jeans and a blazer, St. Pete Mayor Ken Welch glanced at the seat where his late father once sat.

"Right in this room," he reflected, "my father was on this city council, 1981."

Welch is the city's first African American mayor, a third-generation St. Pete resident. He was elected the top leader as the city experiences growing pains amid an exploding population and a housing crisis.

At the center of it all, 86 acres of land sit with an uncertain future. As the end of Tropicana Field's lease with the city approaches, officials are trying to decide how to redevelop the site for the future, while honoring a bruised past.

READ: St. Petersburg officials meeting with potential developers for 86-acre Tropicana Field site

In the 1980s, local officials began the pursuit of bringing a Major League Baseball team to the area. But where would they put a stadium?

Their answer: the Gas Plant District, a Black community, redlined from the rest of St. Petersburg. It was a place Welch once called home.

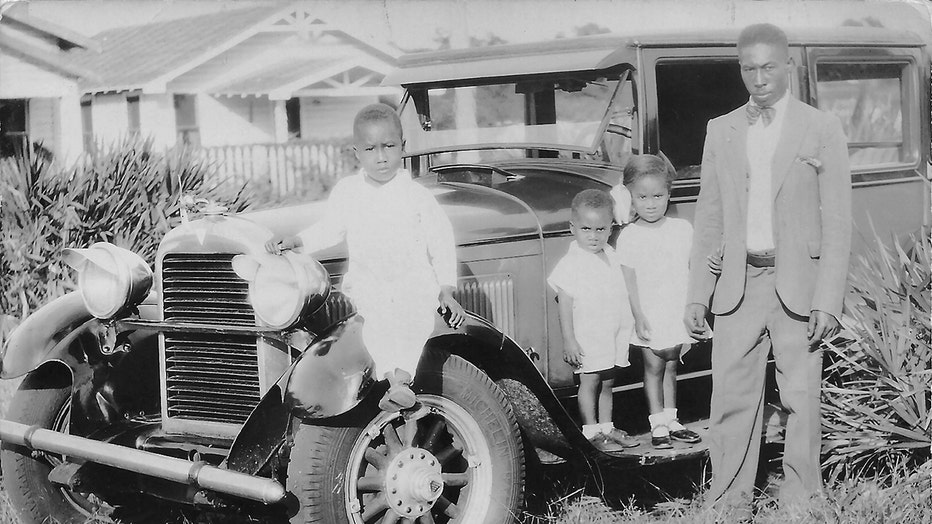

A younger Kenneth Welch is seen pictured with his family (Provided by Mayor Welch)

MORE: Gas Plant District in St. Pete: One of the oldest Black neighborhoods razed for baseball

Residents were promised an economic return for their sacrifice to leave. Years later, it's a promise that has yet to be fulfilled. For Mayor Welch, he doesn't think it's too late to honor it.

It's been 40 years since he, his family, and his community uprooted their homes and livelihood to make space for baseball. Black asphalt, concrete, and an aging dome-shaped building sit where the community once stood.

But the legacy lives on in Gas Plant generations residing nearby.

While recalling his childhood, a smile formed on Welch's face. At that moment, he took a stroll down memory lane, specifically 16th Street South.

Growing up in Gas Plant

Welch was born in 1964. As a child, he admits he didn't understand the politics that created his Gas Plant neighborhood. All he knew was that it was home.

"There was no class difference in terms of income," he explained. "It was the place, through structural racism, that African-Americans had to live in the city by law, but out of that, they created a vibrant community where a kid growing up, like me, never understood the circumstances that discriminated against the community. They made it a nurturing community."

An aerial view of Gas Plant, where the two gas towers are visible. This is before the interstates were built.

The Gas Plant District covered roughly 30 blocks. The northern border was along today's 1st Avenue South and the southern border was 5th Avenue South and Interstate 175. Before the highway, the neighborhood stretched to 7th Avenue South.

This map shows Gas Plant's loose boundaries and where the southern border was before and after the construction of I-175.

The western border was along 16th Street South and extends east to 9th Street South. It was redlined, a community carved out, its residents separated from the rest of the city.

"They’re forced to live in the Gas Plant, no matter if you’re a doctor or a sanitation worker," Welch explained. "You lived in this area."

But out of that came economic growth and well-being among its residents. There were grocery stores, businesses, churches, and homes.

"I often tell the story of walking from my grandfather’s wood yard, which was at 5th Avenue and 16th Street, to our church which was two blocks to the north and two blocks to the east," he began. "Along that route, if I did something wrong, say, borrowed some mangoes from Ms. Brown’s house, by the time I got down that street I was not only reprimanded but when the word got to the church, I was reprimanded and when I was picked up by my parents, I was reprimanded, that kind of community and nurturing for youth was lost."

Welch remembers a younger version of himself, bicycling down 16th Street South – where his grandfather owned a wood yard and his great-aunt owned a restaurant. The wood yard was displaced to make way for I-175. Welch says his church was also displaced – to make way for baseball.

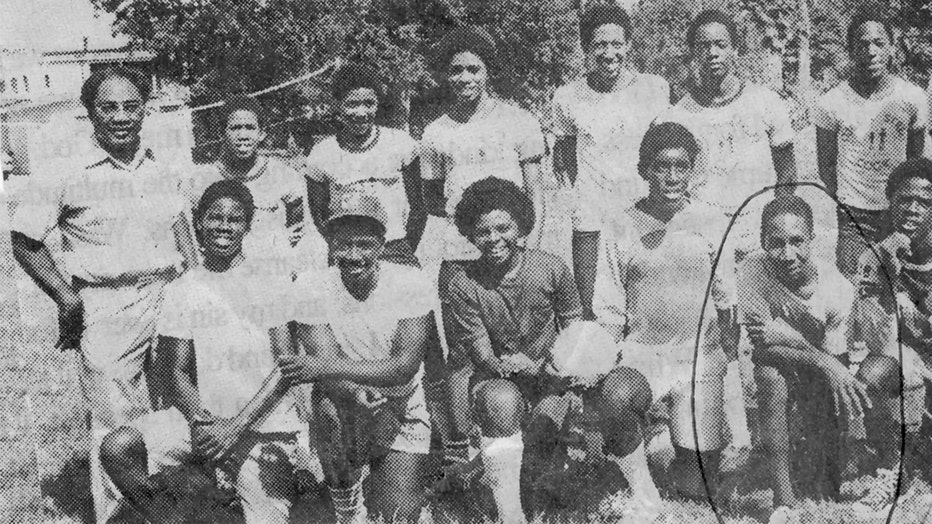

Ken Welch is pictured when he was younger with the Prayer Tower boys. Prayer Tower Church of God in Christ used to be located at 4th Avenue South and 14th Street South. Now, Tropicana Field stands there. (Provided by Ken Welch)

"I would always get the hamburgers there," he said. "It was a whole community of businesses. My uncle, the Brown family, had the dry cleaners. There were grocery stores, corner stores, a lot of churches, and a lot of residences. It was a community."

In the 1970s, city councils began making maneuvers to redevelop the area – not to attract an MLB team, but to bring industrial jobs and multifamily homes to the area. In 1983, that plan was amended to build a stadium.

Bringing baseball to the bay

For Gas Plant residents, uprooting their lives for a new stadium wasn't the first time their neighborhood was impacted. Just a decade before, residents had to move to make way for a new interstate. Welch was around 10 years old at the time.

When city officials began the pursuit of baseball, naturally, there was hesitation as residents thought back to when I-275 and I-175 were constructed. Welch, like his father, believed in the promises that were made.

"Not only the Gas Plant area but the Deuces, as well, was separated by I-275 and I-175," the mayor said. "And, after making that level of sacrifice, now, again, the community is asked. Let’s dislocate the entire community."

His father, David T. Welch, was the second African American to serve on the St. Pete City Council. He initially opposed dislocating hundreds of Gas Plant residents, but he was sold on the idea that it would benefit everyone.

FOX 13 Archives: St. Pete dome controversies

In the days, months, and years leading up to the St. Pete dome groundbreaking, it had its share of legal and financial controversies. Not everyone was on board, including Mayor Ed Cole. During this time, the MLB commissioner stated, ‘St. Petersburg is not among the top candidates' for a home team.

Deuces Rising: Plans approved for revitalization project along South St. Pete's 22nd Ave.

Residents were promised jobs, opportunities for minority business development, and a chance for their businesses to thrive in the new economic environment surrounding the baseball stadium, Welch explained.

"He was really focused on making sure folks got market value, folks had assistance if they had to move their home, making sure folks weren’t left in a hole because they had to move," Welch said. "He really worked hard on that."

As a young adult, Welch watched Tropicana Field rise and the Tampa Bay Devil Rays move into his former home. He hopes the unfulfilled promise to Gas Plant residents could be worked into the new plans for the area.

READ: St. Pete and baseball: A relationship that spans over a century

Honoring that history won't come in the shape of a plaque or a new biking trail, but something that helps build that community back, Welch offered. He is holding out hope the Tropicana Field redevelopment plans can recreate that "nurturing community."

"One way to rebuild that is to fund programs – no matter where they are in the city – to kind of rebuild that nurturing infrastructure for our young people," he explained. "That’s what I think about when I think about ways to rebuild that community."

While the first half of the city's plan came into fruition (bring a professional baseball team to Pinellas County), the second half (the vow made to the Gas Plant residents), never happened.

"Those were the promises that were made," he said. "Some of those businesses were able to relocate and survive, some did not survive. There’s no statute of limitations on those promises. This happened within my generation, 40 years ago. Those promises still need to be honored,

"Get it right"

Over the summer, Welch announced plans to scrap the original batch of Tropicana Field proposals – and start over.

The initial RFP – which was narrowed down to two companies and their proposals – was first issued in 2020, but the landscape of St. Pete has changed since then. At this time, Welch doesn't support using the 86 acres for housing purposes alone.

"I want to see innovation. What can we do in terms of housing on-site and also support housing off-site through this development," he said. "I think there are a lot of ways that folks can be creative and meet the needs for meeting space and office space and affordable housing and transportation and tying into Booker Creek – all those things. Attaching to our innovation center and education hub. I think all those things are possible within those 86 acres. So, I’m excited to see what proposals come back."

Trop redevelopment plans to start from scratch

St. Pete Mayor Ken Welch threw a curveball when he announced the city will restart the process for Tropicana Field's redevelopment and will cancel the current RFP process. Rather than choosing between two developers, the process will start over.

PREVIOUS: St. Pete mayor announces city will nix Trop redevelopment proposals – and start over

There is even more to consider. A study showed St. Pete has a pattern of documented structural racism and minority businesses have been underutilized. Whether the Tampa Bay Rays will be involved in the redevelopment process is still up in the air.

"Our environment has changed in many ways since the initial RFP was issued in 2020. We have to make sure our RFP meets are current values," Welch said in June. "The pandemic has changed the way we work and affected the way we need office space."

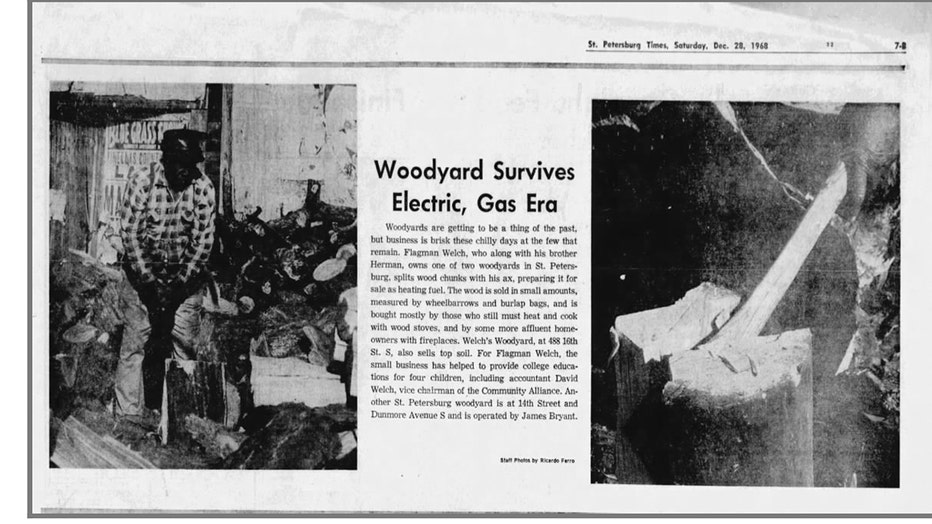

At the start of that press conference, Welch held an ax handle, built at his grandfather's Gas Plant wood yard. He pointed to where the business was originally located.

Mayor Welch holds ax handle -- built by his uncle -- before his June announcement of scrapping the initial RFP proposals and starting over.

Growing up, Welch's grandfather took him and his cousin, Dwayne – who is now an anesthesiologist – to deliver oak, pine, and dirt.

At the time, Welch was about 8 years old, but Dwayne knew how to read maps.

"A paper map. Not Apple maps. Not Google maps," Welch joked.

He remembered the first time he got a tip.

"Grandpa said, ‘You can take the money. It’s a tip for good service.’ That’s the life lessons I learned," Welch said. "Granddad taught us, ‘Yes sir,’ ‘No, ma’am.’ It just showed me the value of education and learning and customer service. That's the life lessons I learned."

This blurb in the St. Petersburg Times discusses Ken Welch's uncle's woodyard. It was published on Dec. 28, 1968.

Without a doubt, Welch brings a unique perspective to the redevelopment process.

"It was a community that took the worst of society and still built a supportive culture within it," he said. "To lose that in the pursuit of baseball and then have those promises of inclusive economic development fall short, all those things really make this an important opportunity to make all those things right and set us on the right course."

From a Gas Plant resident himself to becoming the mayor as redevelopment discussions begin – Welch admits his life has come full circle.

"It’s not weird, it’s providential," he said. "A lot of folks have said that to me. It brings a special insight and perspective to the conversation of someone who grew up here and experienced all those promises. To now be a part of guiding the path forward and telling that story."

When asked what his ancestors would tell him, Mayor Welch said:

"Get it right. Remember and do the right thing."