1920 Ocoee Massacre: Largest U.S. incident of voting-day violence occurred in Florida 100 years ago

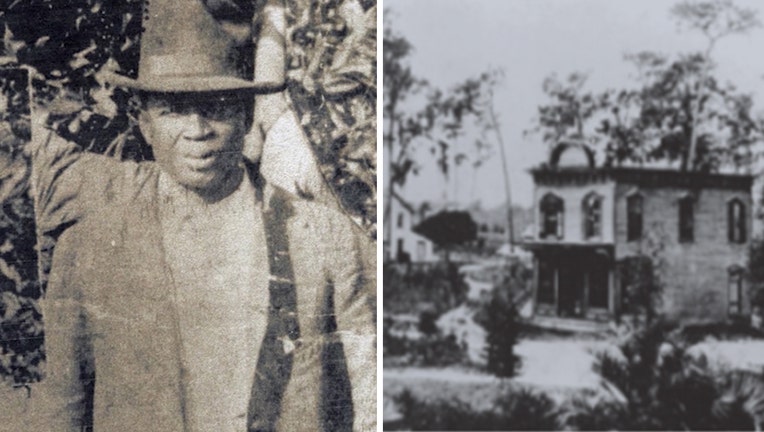

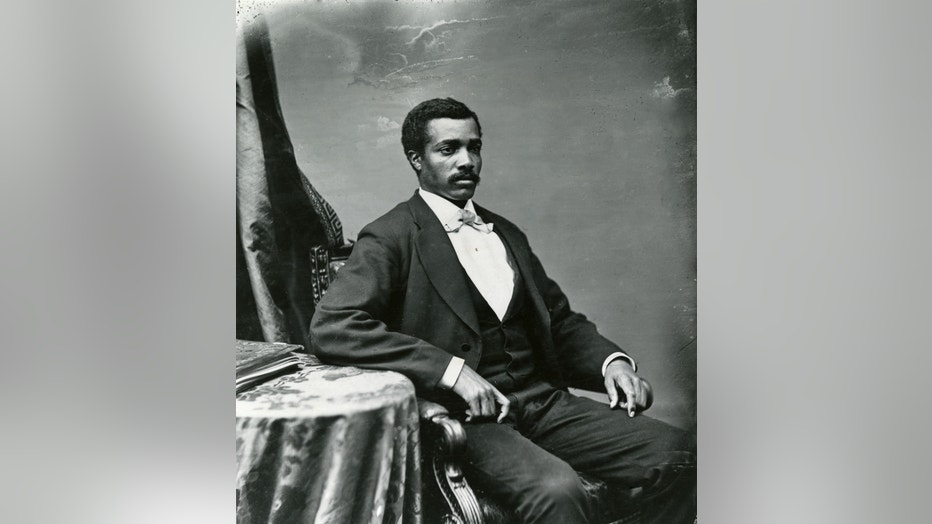

Photo shows July Perry (left), an Ocoee massacre victim, and downtown Ocoee (right) in 1902.

OCOEE, Fla. - One hundred years ago, racism won in Ocoee.

The dark day in Florida's history escalated after one Black citizen tried to exercise his right to vote at a polling location but was turned away on Election Day.

Homes and properties of Black families were scorched, burnt to the ground. At least four Black individuals were confirmed killed -- one of which was lynched, his body hanging from a tree limb for all to see.

To this day, it's unknown how many were murdered due to an intentional attempt to bury evidence of the events and avoid documenting it altogether.

It occurred during a time when Blacks were prospering, owning their own land and making a living, and when there was a drive to register more African-American voters across the U.S., and in Ocoee, which is located between Lake Apopka and Orlando.

But oppression prevailed, and most Black individuals fled in the years that followed due to ongoing terror. None returned for decades.

It was a day that casts a shadow in Florida's past and remains the largest incident of voting-day violence in U.S. history.

READ: 1920 Ocoee Election Day Massacre: Florida museum seeks to shine light on dark day

FLORIDA'S ROOTS IN RACISM

In the decades and days leading up to Nov. 2, 1920, several factors were in play that allowed an event like the Ocoee massacre to occur. The deadly riot wasn't isolated in a vacuum -- it was a longtime building.

One of those factors, and the most obvious, was enslavement.

The Underground Railroad was known to guide Black slaves north into Canada, but nearly two centuries earlier, the Spanish terrority was a safe haven.

Map of St. Augustine in 1783. In 1513, Ponce de Leon went on his search for the Fountain of Youth, and was joined by free Africans during his quest. By 1526, those enslaved by the Spanish helped build St. Augustine, the first permanent European settl

Back in 1687, the first set of slaves were welcomed by the Spanish colony of Florida: eight men, three women and a 3-year-old child. Even more followed seeking refuge in La Florida.

In 1693, Spain granted them freedom, and made La Florida a sanctuary for enslaved Africans as long as they converted to Roman Catholicism and pledged allegiance to the Spanish king.

However, the rules changed after the Adams-Onis Treaty, when Spain ceded the territory to the U.S. By 1845, Florida was admitted into the Union.

Fort Mose was the first legally-sanctioned free-black community in the U.S. Today, it is a designated state park in the historic Florida city, St. Augustine. (City of St. Augustine)

Before the Civil War, in the mid-1850s, a man named Dr. J.D. Starke moved into present-day Ocoee, starting the first settlement in the area with a group of slaves.

Photo of Starke Lake before 1880, and prior to development. (City of Ocoee)

After President Abraham Lincoln won the presidential election, Florida seceded from the Union on Jan. 10, 1861. By February, they joined other southern states to form the Confederate States of America. Eventually, that led to The Civil War and Emancipation Proclamation, which freed all slaves in the southern states.

According to the U.S. National Archives, about 179,000 Black men served the Army and 19,000 served in the Navy. Nearly 40,000 died over the course of the war. Among those, about 30,000 died from an infection or disease.

Even though the 13th Amendment, ratified in 1865, abolished slavery in the country, it gave rise to the Jim Crow Laws. In Florida, that impacted intermarriage, cohabitation, education and juvenile delinquents involving white and Black individuals.

Photo shows Bluford Avenue and downtown Ocoee in 1902. (City of Ocoee)

After the Civil War, Confederate veterans began moving to the Ocoee area, including Captain Bluford M. Sims, a Tennessee native. He purchased land from Starke and grew the first-known citrus nursery in the U.S.

The area of land where Sims grew those citrus groves is where most of today's downtown Ocoee exists. He also plays a role in Black-owned land in the days after the massacre.

THE RED SUMMER OF 1919

The Jim Crow Laws dominated for years, even during the Red Summer, when lynchings and race riots increased over the course of several months in 1919.

That year, a convicted molester in Jacksonville was moved to a St. Augustine jail for safety. However, a white mob overran the Jacksonville jail and ended up breaking out two Black men who were imprisoned on a separate incident.

Both were strung up, shot, tied behind cars and dragged around town.

The Red Summer took place during a time when soldiers returned from WWI, including Black soldiers.

Young Black men enlisted in WWI, giving them the opportunity to witness parts of the world where racism wasn't as rampant as it was in the U.S.

Portrait of unidentified WWI soldier holding a U.S. model 1917 Enfield rifle. (Florida State Library and Archives)

According to the American Battle Monuments Commission, Florida provided over 42,000 to the U.S. armed services during the war. More than 13,000 were African-Americans from Florida. Not only did they return home after fighting for their country, but they returned with a renewed interest in equality.

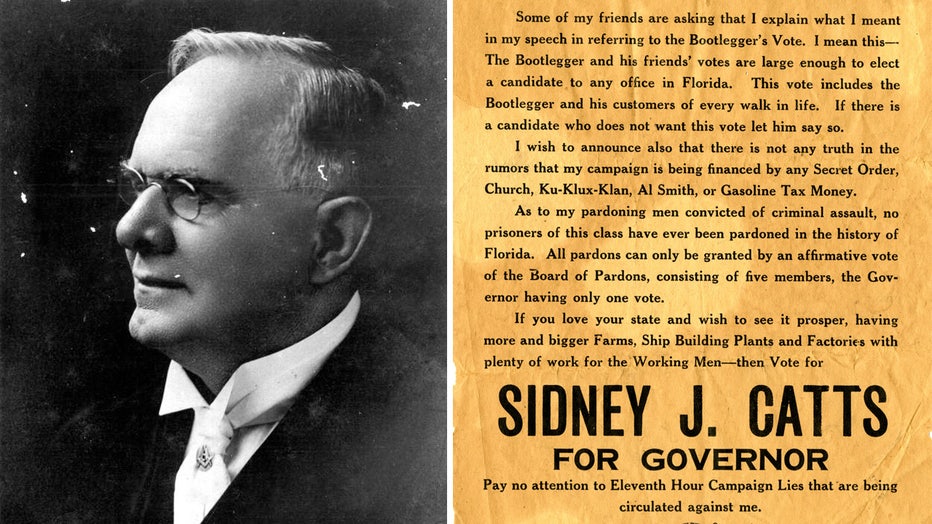

Sidney Catts was the 22nd governor of Florida, serving from 1917 to 1921. He publicly called black residents as part of "an inferior race" and refused to criticize two lynchings in 1919. (Florida State Library and Archives)

When Black veterans returned to America, they "were seen as a particular threat to Jim Crow and racial subordination," reports the Equal Justice Initiative. The 1919 racially-motivated attacks, in many places, were initiated by white servicemen. At least 13 veterans were lynched across the U.S. after WWI.

The slaves who settled in the Ocoee area with Starke left after the Civil War. By 1920, the African-Americans living there were not the individuals formally enslaved in that area.

RACIAL TENSIONS DURING ELECTION YEAR

The 15th amendment was adopted into the constitution in 1870, which states:

"The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

However, that didn't stop the South from creating their own rules to stop Blacks from voting. Florida adopted several loopholes, too.

After slaves were freed, many were uneducated, which gave rise to the literacy test requirement to vote. Many were also poor, which was part of the motivation behind the poll tax.

At the time, Florida was one of four states that relied on the poll tax to impede black voting. It was one of the first in the nation to adopt it.

It wouldn't be until the Voting Rights of 1965 when those barriers to stop Blacks from voting were outlawed

Josiah Walls was Florida's first black member of the Congress after winning the election in 1870. He was a former slave and Union solder from Alachua County. For the next 116 years, he was the only black member of Congress from Florida. (Florida State Library and Archives)

During the 1920 election year, there was a big drive for Black voter registration in Florida since they historically voted Republican. The parties' platforms were different at the time.

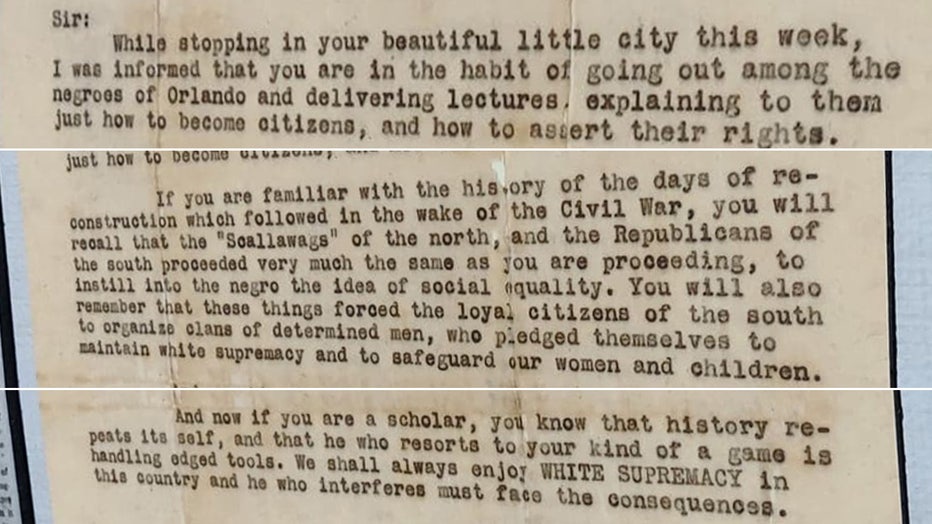

In Orlando, Judge John M. Cheney, a white Republican who was running for Senate at the time, helped lead that campaign. On Sept. 20, 1920, Cheney, and attorney W.R. O'Neal received a letter from the Ku Klux Klan, threatening them to stop giving lectures about voting in the Black community.

The letter read in part, "We shall always enjoy WHITE SUPREMACY in this country and he who interferes must face the consequences."

The bottom of the letter copied the local KKK branch, telling the members, "Watch these two."

Letter sent from the Grand Master Florida of the KKK to W.R. O'Neal and Judge John Cheney. This can be viewed at the Orange County Regional History Center.

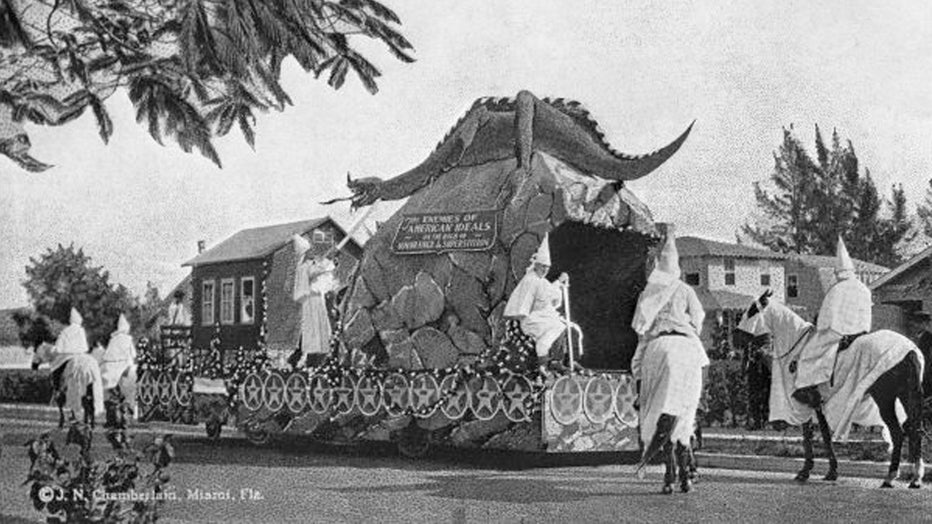

As there was a rise in Black voter registration, there was a rise in membership for the KKK, especially in Central Florida.

Before Election Day, the KKK held marches throughout the state. There were hundreds in the streets of large cities, such as Jacksonville and Orlando.

In this 1920 photo, a Ku Klux Klan float is seen in parade along Flager Street in Miami. (Florida State Library and Archives)

These events between 1850 to 1920 led up to the boiling point that spilled over in Ocoee on Election Day.

WHEN MOSES WENT TO THE POLLS

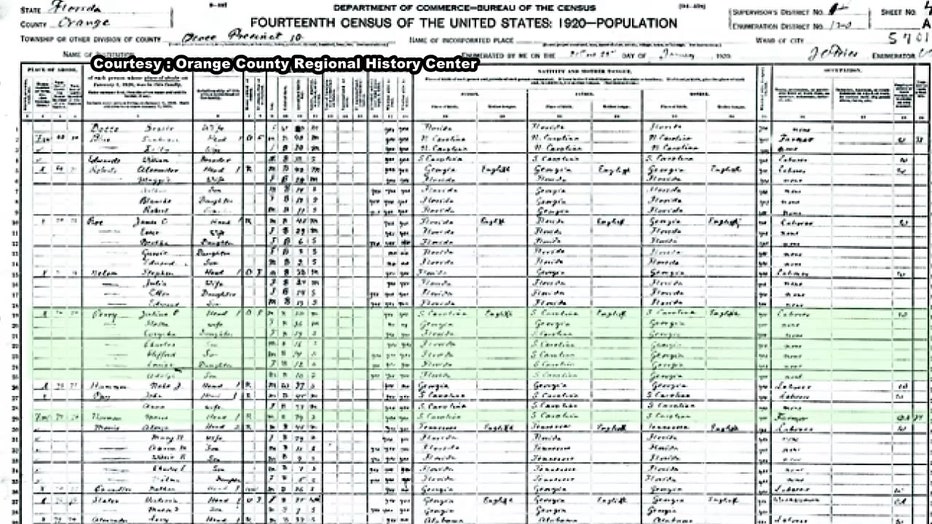

Ocoee was not yet an incorporated area of Orange County, and didn't officially become a city until 1925. At the time of the massacre, it fell under Precinct 10, which was part of the county's voting district.

There were 11 Black residents in the unincorporated area back in 1870, according to the census. By 1885, there were 15. That number grew to 255 Black individuals by 1920, with 560 white residents.

Despite the Jim Crow Laws, Blacks were working, saving money, and buying their own properties in the early 1900s. There was an obvious growth in economic competition within the African-American population.

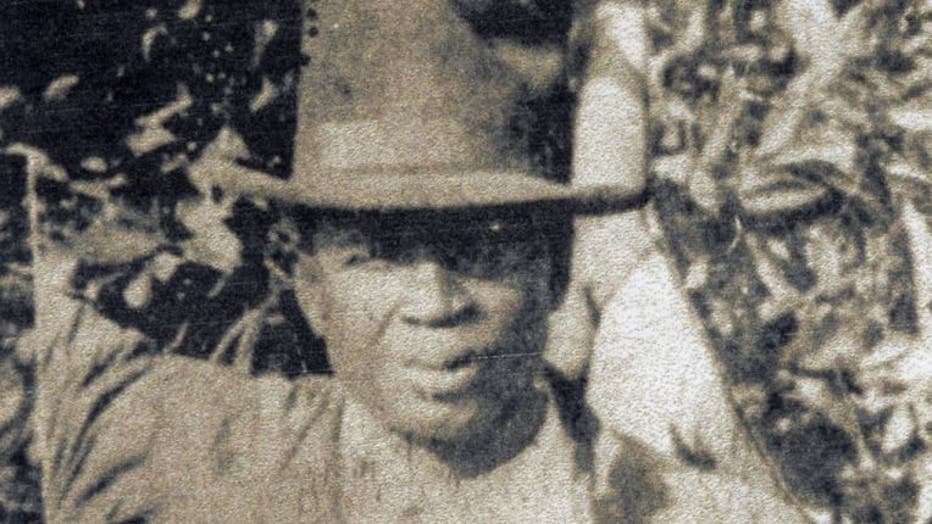

Two of the main individuals whose names are associated with the Ocoee massacre are Moses Norman and July Perry. Both were Black land owners and labor brokers. Essentially, they served as a go-between for Black laborers and white employers.

Norman had moved to the area from South Carolina and was living on Sims' property while working for him, which was not uncommon for any worker -- Black or white.

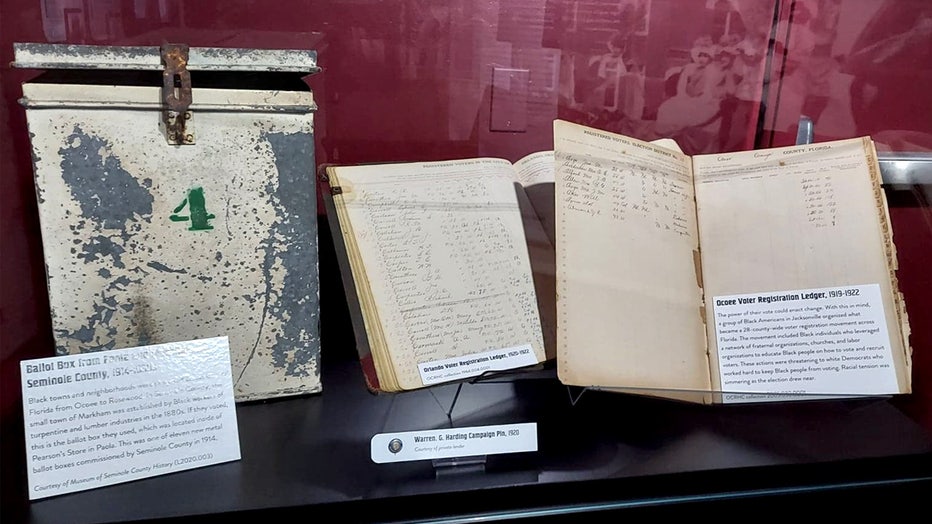

Photo shows an Ocoee voter registration booklet and a ballot box from Seminole County during the early 1900s. They can be viewed at the Orange County Regional History Center's exhibit on the Ocoee massacre.

The events that immediately followed Norman's attempt to vote on Nov. 2, 1920 are essentially foggy. There are different accounts, mainly because there was a deliberate attempt to not only avoid documenting evidence that occurred that night, but to destroy it.

According to the Orange County Regional History Center, most historical accounts agree it started with Norman trying to vote, but was turned away for allegedly not paying his poll taxes.

Later that night, after the polls closed, a group of armed white men arrived at Perry's home, in search of Norman.

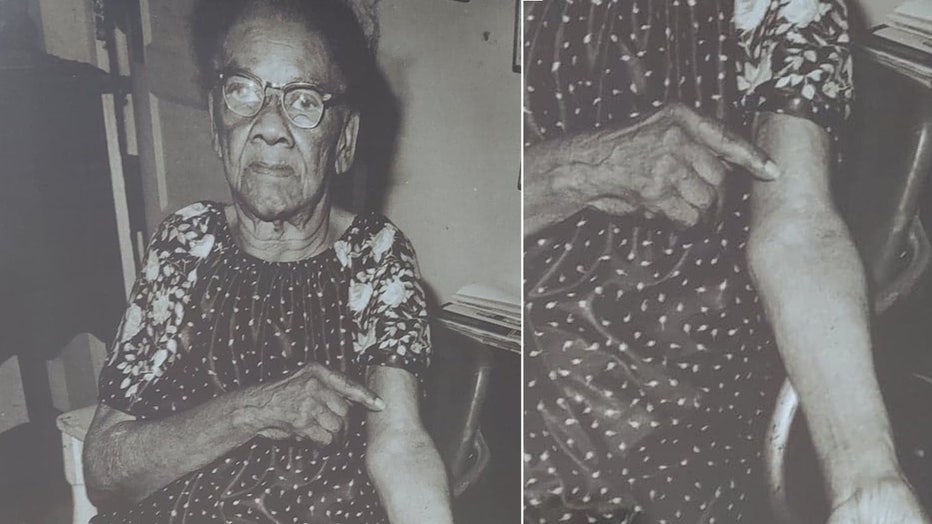

It's unclear how the encounter escalated, but a shooting broke out. Two white men, who were law enforcement officers, died, and Perry was badly injured. Perry's wife and daughter escaped from the back of the home.

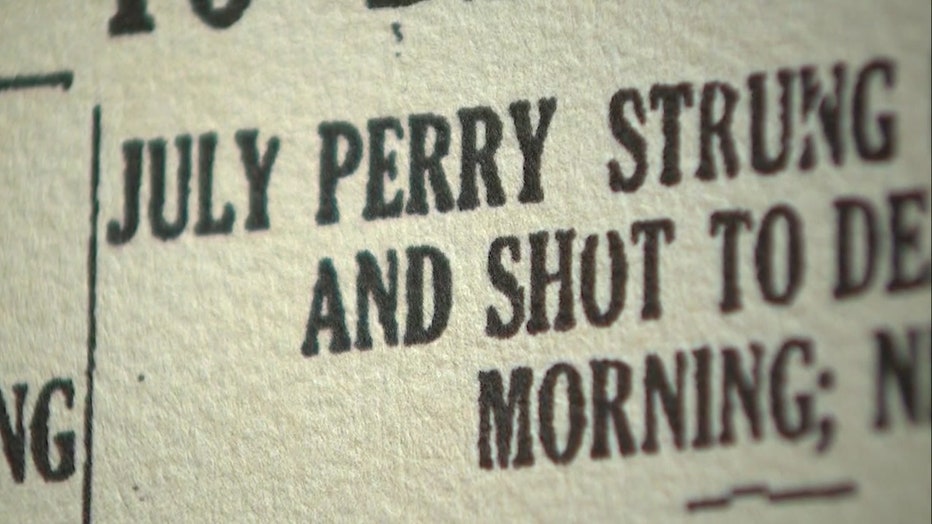

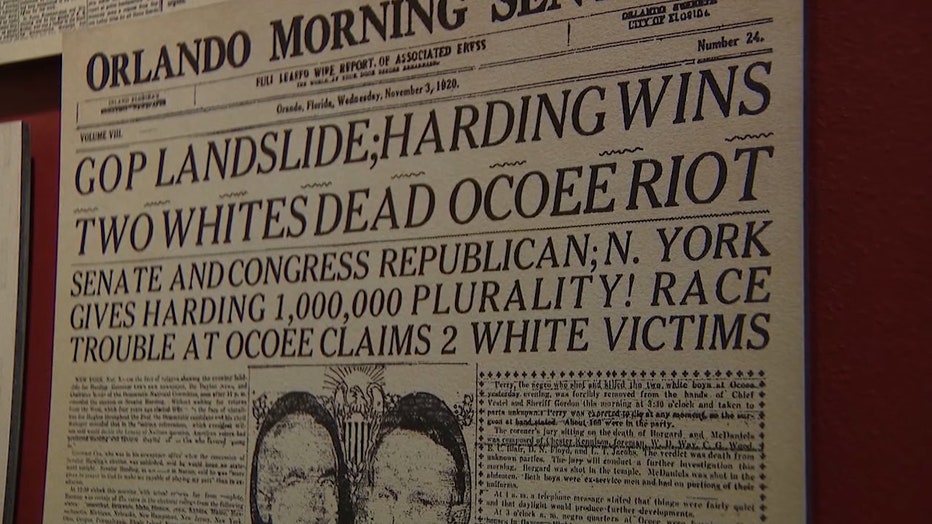

Newspaper clipping following the Election Day Massacre. (Orange County Regional History Center)

Perry received some level of medical attention, and was taken to the Orange County Jail in downtown Orlando. According to the state of Florida's coroner's request that took place between Nov. 3-4, a white mob overpowered the single jailer who was left to guard Perry.

The mob took Perry, beat him, shot him and hung him from a tree. Perry's body was eventually moved to the Greenwood Cemetery, where he was buried.

That night, the mob starting setting Black-owned homes on fire, as well as churches and a fraternal lodge. Some accounts say up to 60 Blacks were murdered, but the Orange County Regional History Center recently confirmed four deaths through public records. State death records were not kept after the deadly riot.

The Carey Hand Funeral Home was in charge of handling the bodies. A memoranda exists that reads, "three colors persons buried in...caskets in one grave together."

Even though photography was available in 1920, no photographic evidence was taken the night of the massacre, or its aftermath.

As for Norman, he fled from Ocoee and lived in other parts of Florida, before leaving for New York City to live out his days.

Photo of July Perry, who was hung during the Ocoee Election Day Massacre (Orange County Regional History Center)

BLACKS FLEE OCOEE

There were parts of the Black community that remained untouched, but a portion was burned to the ground.

In the following days, a group of white ex-servicemen surrounded Ocoee to restore order. Afterwards, according to an Orlando Sentinel article at the time, they received a dinner at a hotel for helping during the "Ocoee trouble."

Perry's wife, Estella, and daughter, Coretha -- who had a bullet wound in her arm -- were taken to Hillsborough County Jail in Tampa, supposedly for their safety.

Coretha Perry, daughter of July Perry, is shown in this Orlando Sentinel photo that is on display at the Orange County Regional History Center. She points to a scar from a bullet wound.

There are historical accounts that say people showed up at the jail to gain access to them, but were turned away.

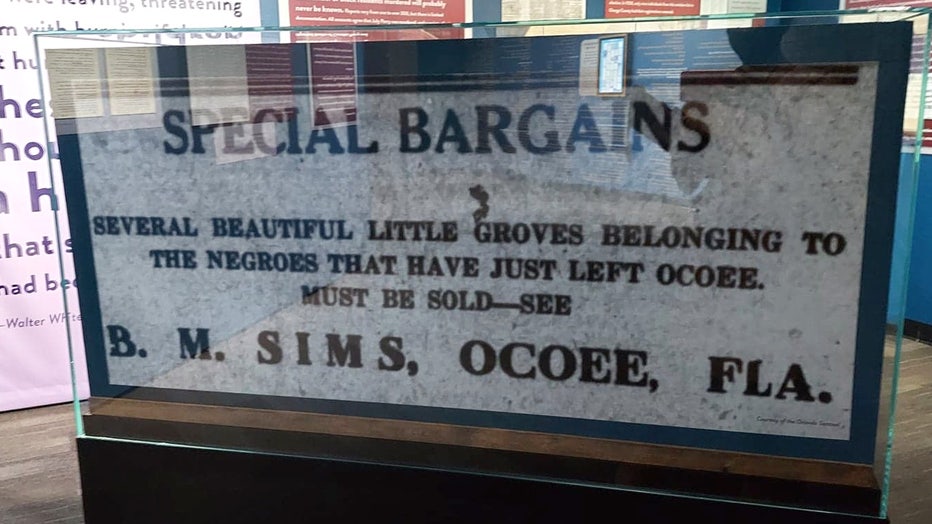

After Perry's death, neither Estella nor Coretha were appointed the executor of the estate. Instead, it was passed onto Bluford Sims, one of the early settlers who served the Confederate army.

It's unclear how he obtained the property, but he did place an advertisement in the Orlando Sentinel stating he was selling the property that belonged to "Negros that just left Ocoee."

One of the ads from Bluford Sims on display at the Orange County Regional History Center

His ad wasn't the only one selling off Black properties. Within two weeks of the massacre, there were advertisements in Orlando and Miami offering the sale of groves and land.

Eventually, Sims was deemed incompetent, likely due to old age, and could no longer handle the estate affairs. It was then passed on to his daughter-in-law, Eva Sims.

Perry's family filed a lawsuit seeking compensation, and the court ordered her to provide property accounting, but she never did.

To this day, although there are some deed records, it's unknown whether, if any, Blacks were compensated for their property.

Walter White, a light-skinned Black man, later became the NAACP chief secretary. His light complexion allowed him to pass for a white man and investigate dozens of massacres, including the one that took place in Ocoee. (Library of Congress)

Within two days the massacre, a coroner's request into Perry's death, as well as the two white men who died in the initial encounter, found that their deaths were committed by unknown parties.

Shortly after, Walter White with the NAACP headed to Ocoee to pose as a Black real estate agent and gather information. He later gave testimony in December to the U.S. House of Representatives and Census Committee.

Between Nov. 18-29, the Department of Justice launched an investigation, but only to determine whether there was any election fraud.

On Nov. 30, a grand jury reported their findings, but to this day, the full report remains missing. Perry's wife and daughter did not face charges related to the deaths of the two white men searching for Norman. They weren't released from the Tampa jail until 27 days after Election Day.

After that, the family spent 12 years fighting land disputes and lawsuits over their Ocoee property. On March 7, 1932, seven relatives each received $125.90 for the loss of their home, possessions, about 30 acres of land, and their loved one, July Perry.

Ocoee's 1920 census shows there were 255 Black individuals living in 78 family units, and there were a total of 560 white individuals on record. By 1930, the census records listed only two Black servants in Ocoee. (Orange County Regional History Center)

Eventually, all Black residents left the area as they faced ongoing terror.

In one case, George Betsey, an African-American living in Ocoee, was found injured, tied to a light post because he talked "too much about the trouble at Ocoee last November."

In other cases, dynamite was thrown into homes while other Blacks were beaten and threatened.

It would be at least another 50 years before an African-American moved to Ocoee.

LESSONS TODAY

This year marks 100 years since the massacre.

In 2018, the city of Ocoee issued a proclamation during a commission meeting in remembrance of the tragic event:

"In 1920, the historical record shows that African-American residents of West Orange County in and around what later became the City of Ocoee were grievously denied their right to vote, their civil rights, their properties, and their very lives in a series of unlawful acts perpetrated by a white mob and government officials."

The proclamation can be read here.

Last year, a historical marker was placed outside the Orange County Regional History Center, located in downtown Orlando, which honors July Perry. It's the first physical memorial to acknowledge his lynching.

This year, the city has several events planned to honor the victims and descendants of the massacre. The list of events can be viewed here.

(Orange County Government)

The historians at the museum spent the past three years researching the Ocoee massacre and recently opened the most in-depth and comprehensive exhibit on the topic.

While the museum acknowledges there are multiple of version of what occurred that day, they spent endless hours confirming information through census records, property records and other official documents.

For instance, an interactive map in the exhibit shows the land owned by Black residents in Ocoee before, during and after the massacre. However, to this day, it remains unclear what African-Americans received in return for their property.

"There are land deeds, but land deeds and the transfer of those don't always show you the full picture," explained Pam Schwartz, the museum's chief curator. "It could've been, 'This is $10 to make the deed official. I'm going to give you $200 over here on the sly. Here's $10, I'm going to let you keep your life.'"

Based on information the historians found, the properties previously owned by those Black Ocoee residents would have been valued at over $9 million today, Schwartz explained.

‘Unthinkable’: July Perry’s great-niece reflects on Ocoee massacre legacy

In 1920, on Election Day in Ocoee, July Perry was captured, taken to jail, lynched and hanged after another Black man in the community tried to vote. His great-niece, Sha'ron Cooley McWhite, says even though the tragic event occurred a century ago, it still causes her family pain today. 'It’s unthinkable but the most important part is not how he was killed. It’s why he was killed. That’s what we need to talk about.'

But for Schwartz, probably the most alarming lesson from the research, she said, was a lack of justice.

"Nobody, nobody was convicted in this event," she said. "An entire community burned to the ground and people murdered and nobody was found guilty of that. Nobody paid for it -- and that local government had a hand in covering that up and allowing it to happen.

Over the summer, Gov. Ron DeSantis signed House Bill 1213 into law, creating a task force that would recommend the most accurate and appropriate ways to teach the Ocoee massacre in classrooms.

Ocoee election day riots to be taught in Florida schools

House Bill 1213, signed into Florida law over the summer, will make sure public school students learn about the largest incident of voting day violence in U.S history, which happened in Ocoee and resulted in the lynching of a Black man.

An earlier version of the bill included over $2 million in compensation for Ocoee victims and their descendants, but that language was replaced with the education curriculum out of concerns that the reparations portion wouldn't pass.

The museum is also building a separate digital guide for teachers to use. Schwartz said they are seeking donations to help develop the classroom curriculum.

The History Center's exhibit also includes oral histories from descendants of the Ocoee victims.

"They're hardworking, they're entrepreneurs, they're moving and they're shaking, and they're all focused on leading a really wonderful life," Schwartz described. "I think there's definitely a legacy left, not only this dark legacy of having this in your family history but there's also the beautiful legacy of people who somehow rose above and beyond this."

Perry's great-grandchildren live in Tampa, and have since launched the July Perry Foundation, aimed at supporting "underserved population whom have a desire to become entrepreneurs, land owners, land developers, architects, and all interested in the process of agriculture, multi-unit housing and commercial building development."

PREVIOUS: Ocoee massacre to be taught in Florida schools, according to newly-signed law

Schwartz said the events occurring this year, such as the Black Lives Matter movement, appear to show the same struggles seen even a hundred years ago.

"If you look at the themes: voter rights, gentrification and trying to move people from their home," she explained. "These issues of people of legal authority and the interactions of law enforcement with the Black community...look at how those themes from 100 years ago and those events reflect on the history we are currently living."

If you're interested in visiting the Orange County Regional History Center's Ocoee massacre exhibit, you can learn more by visiting the museum's website. It will run through Feb. 14, 2021.

Those who are interested in donating to the History Center can contact the museum at 407-836-8500.

The historical facts discussing the Ocoee massacre and its aftermath in this article were provided by the historians of the Orange County Regional History Center.