Olympic athletes who raise fists, kneel during national anthem won't face punishment in US trials

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. (AP) - The U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee will not sanction athletes for raising their fists or kneeling during the national anthem at Olympic trials, previewing a contentious policy it expects to stick to when many of those same athletes head to Tokyo this summer.

The USOPC released a nine-page document Tuesday to offer guidance about the sort of "racial and social demonstrations" that will and won't be allowed by the hundreds who will compete in coming months for spots on the U.S. team. The document comes three months after the federation, heeding calls from its athletes, determined it would not enforce longstanding rules that ban protests at the Olympics.

The International Olympic Committee's Rule 50 is an ongoing source of friction across the globe. Many U.S. athletes have spearheaded the call for more freedom in using their platform at the Olympics to advance social justice causes. But others, both in and outside the U.S., balk at widespread rule changes that they fear could lead to demonstrations that sully their own Olympic experiences.

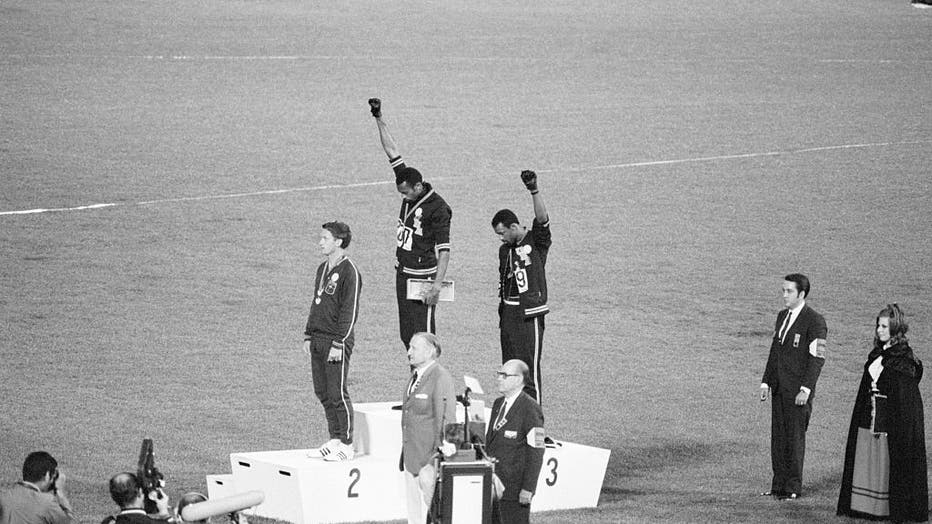

The wide-ranging debate traces its most-visible roots to the ouster of U.S. sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos from the 1968 Games. Their raised fists on the medals stand in Mexico City led to the seminal snapshot of social protest in sports history.

Tommie Smith and John Carlos, gold and bronze medalists in the 200-meter run at the 1968 Olympic Games, engage in a victory stand protest against unfair treatment of blacks in the United States.

With guidance from its recently formed Council on Racial and Social Justice, the USOPC released a list of do's and don'ts as part of its document. The list of allowable forms of demonstration included holding up a fist, kneeling during the anthem and wearing hats or face masks with phrases such as "Black Lives Matter" or words such as "equality" or "justice."

Not allowed are hate symbols, as defined by the Anti-Defamation League, and actions that would impede others from competing, such as laying down in the middle of the track.

The document takes pains to define as much as it can, including making clear that acceptable demonstrations should involve "advancing racial and social justice; or promoting the human dignity of individuals or groups that have historically been underrepresented, minoritized, or marginalized in their respective societal context."

It sets out a process by which cases that step outside the rules can be decided. It also makes clear that while the USOPC will not sanction athletes for many actions, it cannot "prevent ... third parties from making statements or taking actions of their own, and that each Participant must make their own personal decision about the risks and benefits that may be involved."

Those third parties could include the IOC itself. The body that runs the Olympics is in the process of its own review, led by an athletes’ commission, that could lead to tweaks in Rule 50. It is not expected to go as far as what the USOPC is doing. That review is expected to be complete next month, and the USOPC could adjust its guidance if needed.

But the USOPC's original decision — announced in December — that it would not punish athletes who run afoul of Rule 50 in Tokyo drew a line in the sand that sets the stage for possible conflict. Under many circumstances in the past, a nation's Olympic committee has been expected to deliver sanctions to athletes on its team that run afoul of rules at the Olympics. The USOPC has made clear it won't do this in many cases that fall under Rule 50.

"I have confidence you’ll make the best decision for you, your sport and your fellow competitors," Sarah Hirshland, the CEO of the USOPC, wrote in a letter to athletes to address the new guidance.