St. Pete and baseball: A relationship that spans over a century

FOX 13 Archives: Tampa Bay Devil Rays first home-opener

On March 31, 1998, the Tampa Bay Devil Rays finally held the team's first home-opener to a packed stadium -- eight years after Tropicana Field officially opened. The team played against the Detroit Tigers and lost 11-6.

ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. - Overlooking Tampa Bay, Rowdies fans congregate in a stadium where Major League Baseball spring training thrived for decades, but the Tampa Bay Rays wasn't the only team to use the field.

From Sunshine Park to Al Lang Stadium, seven teams had quite the view in St. Petersburg over the years. In total, 193 Hall-of-Famers played ball in the city.

Photographs of players training among the palm trees, with Tampa Bay as the backdrop, were used to promote the area to the rest of the world, giving exposure to a sleepy city and turning it into a tourist destination.

St. Pete's relationship with baseball dates back to the early 1900s, starting in a little neighborhood just north of today's Vinoy Renaissance Hotel.

Spring Training in St. Petersburg

Spring training began in 1914 at a ballpark that doesn't exist anymore, near Coffee Pot Bayou.

Local businessmen launched the group St. Petersburg Major League and Amusement Company and raised funds to attract a team for spring training in St. Petersburg.

It worked. The St. Louis Browns came down to the Sunshine State and played at Coffee Pot Bayou Park, also called the Sunshine Park, according to Preserve the Burg.

In February 1914, the first spring training game took place between the Browns and Chicago Cubs. The Cubs won.

The Browns were in St. Pete for only a year. The team would later become the Baltimore Orioles.

A lot of the credit goes to Al Lang, a two-time mayor of St. Pete who helped convince the Browns to train in his city. In the following year, the Philadelphia Phillies made the same move.

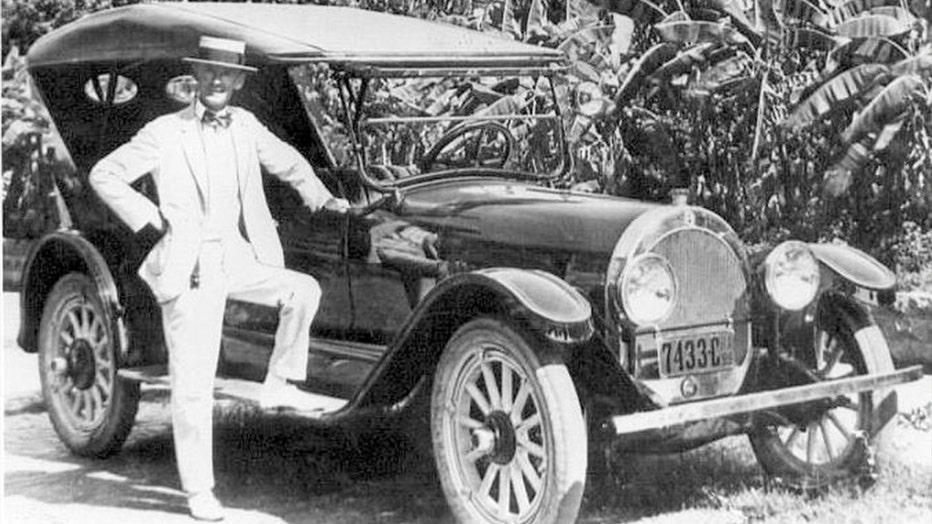

Mayor Al Lang (Provided by St. Petersburg Museum of History)

Lang moved to St. Pete from Pittsburgh, for health reasons, and became the city's biggest advocate. It helped that he was also an avid baseball fan.

"Al Lang was the guy who came along and said, 'Well, first of all, we're going to clean up the city. We're going to make it desirable," explained Rick Vaughn, former Tampa Bay Rays vice president of communication and author of "100 Years of Baseball on St. Petersburg's Waterfront". "But we're also going to use baseball to help us get the story out about the great things our city has to offer. That's not the whole story, of course, but it is a good part of it."

New book captures connection between baseball and St. Pete

Rick Vaughn has a lifetime of baseball memories, 30 of which he has spent in Tampa Bay. It led him to author a book titled "100 years of Baseball on St. Petersburg's Waterfront."

READ: Tampa Bay Rays retiree authors book on how 100 years of baseball helped shape St. Pete

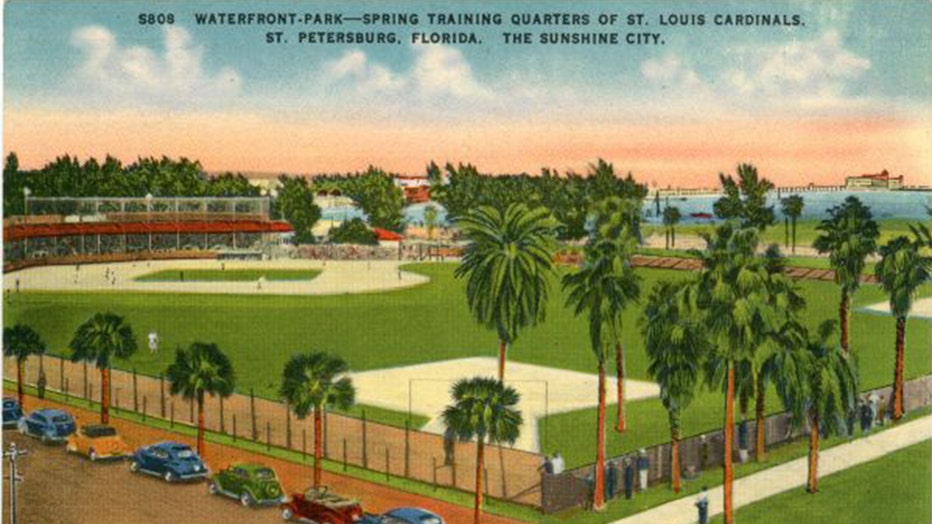

By 1922, city leaders moved forward with expanding the baseball footprint. The Waterfront Park was built north of the present-day site of Al Lang Stadium and the Boston Braves played in front of 5,000 fans.

The New York Yankees started playing there in 1925, all the way until 1961 – except during WWII when the government wouldn't allow travel, Vaughn said. Concurrently, the Arizona Cardinals also came to St. Pete for spring training in 1938 and left in 1997.

Postcard showing Waterfront Park (Archives from State of Florida)

Waterfront Park was knocked down in 1947. Al Lang Field came along at that point, about a block away.

"The New York writers would joke with [Lang] all the time that St. Petersburg was discovered in 1925 – which was the year the Yankees came," Vaughn said. "They used to give him a lot of grief."

The Mets took the New York media baton in 1962, and they didn't leave the spring training home until 1987.

"It really had such an impact on shaping the city," Vaughn told FOX 13. "Yes, it was spring training. Yes, the numbers really don't count for spring training but when you think about the iconic images that came from St. Pete – baseball, water in the background, the palm trees – those images did a lot to promote baseball and baseball was very smart to ride that for a long time."

Then, Al Lang Stadium was constructed.

READ: Baseball broadcast on TV for first time in 1939

"In 1976-77, the ballpark was built. But the year before, baseball stayed in St. Pete even though the stadium had been knocked down, it was being rebuilt," Vaughn said. "They played at Campbell Park. I think there were 13 major league spring training games played on that field while Al Lang Stadium was being built.

Today, the tradition of spring training in Florida spans 130 years. All but six MLB teams train at 35 different sites across the Sunshine State.

The cities with the most years of spring training are Tampa and St. Petersburg.

Iconic sluggers who played on St. Pete's waterfront include Babe Ruth, Jackie Robinson, Yogi Berra, Lou Gehrig – the list goes on.

Baseball and Civil Rights

When Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in 1947, he became the first African American in the 20th Century to play in the modern major leagues. On April 15 of that year, he made his debut for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

"I think a lot of people felt like, you know, things were going to be better in every respect for Blacks playing or people of color, for that matter, playing baseball," Vaughn explained, "and that really wasn't the case especially when it came to the South and spring training."

Jackie Robinson, in military uniform, becomes the first African American to sign with a white professional baseball team. He signs a contract with the minor league club in Montreal, a farm team for the Brooklyn Dodgers. (Getty Images)

Even in the early 1960s, it was codified into state law that players of color could not stay in the same hotel as white players. That came to a head in St. Petersburg.

Dr. Ralph Wimbish, an African-American living in the Gas Plant District, opened his home to Black players. So did, Dr. Robert Swain, the first Black dentist to build a clinic in the city. Next door, he built an apartment that housed players.

According to Dr. Swain's obituary in the St. Petersburg Times, he housed Black players for the Yankees and Cardinals. Famous players like Bob Gibson and Elston Howard stayed there.

By 1960, both doctors had a change of heart, believing it was time for hotels in Florida to desegregate, forcing the responsibility onto team owners. At this point, 13 of 18 major league teams were training in the Sunshine State.

"In the early 60s, [Dr. Wimbish] finally said, 'You know what, I love these guys, but I'm not going to do this anymore because we're really not doing anything to stop this situation. We need to end this,'" Vaughn explained. "The Yankees ended up leaving in 1962 and part of the reason was, I think, because they wanted all their players to stay under one roof, and they weren't able to do that at St. Pete. So, the pressure started to mount."

The Tampa Bay Rays gather on the pitchers mound in the fourth inning against the Boston Red Sox on April 16, 2010 at Fenway Park in Boston, Massachusetts. The Tampa Bay Rays wore the number 42 to honor Jackie Robinson. (Photo by Elsa/Getty Images)

In 1961, an incident occurred involving the Cardinals and an annual breakfast event with the Chamber of Commerce in downtown St. Pete. Bill White, who was the first Black play-by-play announcer in the major leagues and the first African American to become the president of the National League, was one of those players.

According to "Journal of Sport History":

"White and his black teammates were excluded from the invitation list to the St. Petersburg, Florida "Salute to Baseball" breakfast. City and team officials maintained they had not intended the breakfast to be a white-only engagement and the team invitations were meant to include all players. But White and the others had not found the invitations to be so explicit. No longer willing to accept excuses for discrimination, White used the incident to publicly condemn the discriminatory racial policies at spring training locations in Florida."

Ultimately, the Cardinals purchased a hotel near the bay and placed all players under one roof.

"The great thing about that was that some of the white players who were staying on their own with their families, they moved to the hotel," Vaughn added. "So, it was a really nice showing of solidarity there."

Vaughn said when he spoke to White, the discriminatory practices boiled down to two factors:

"One, all of us players, we just wanted to win. We just wanted everybody together. It was about, which is a great thing about sports, how it does bring people together. And then he brought up a good point. Arizona was attempting to steal some of these teams away from Florida just because of that issue."

Within a few years, the teams who held spring training in Florida brought colored and white players together under the same living arrangements.

"It didn't cure the ills of the civil rights issues, but it started it for baseball," explained Vaughn. "I kind of felt like St. Pete was kind of like this flashpoint for that to start happening for baseball. There were a lot of positive things that came out of the game for this city and I think it’s important for people not to forget that."

Attracting an MLB team

The city's history of baseball and brainstorms ways to ramp up downtown's economy eventually led to serious conversations about luring a professional team to the Pinellas peninsula.

But first, they needed a stadium.

In 1977, the Pinellas Sports Authority was created by the Florida Legislature. The group's purpose was to search for a suitable site and bring a team to the area.

At one point, leaders considered the waterfront area where Al Lang Stadium is located. They also discussed the Gateway area – the land south of Howard Frankland and Gandy bridges. In the early 1980s, south of Gateway was not developed like it is today, explained Rick Mussett, the former Senior City Development Administrator and Planning Director for the city for nearly 35 years.

"Downtown St. Pete was nowhere near like it is now. There was nothing going on," he explained. "We tore down the old pier. There were a lot of problematic things that were going on, limiting development. The concern was if the stadium got built out [in the Gateway], all the collateral development that goes with a stadium would be there and downtown would continue to rot."

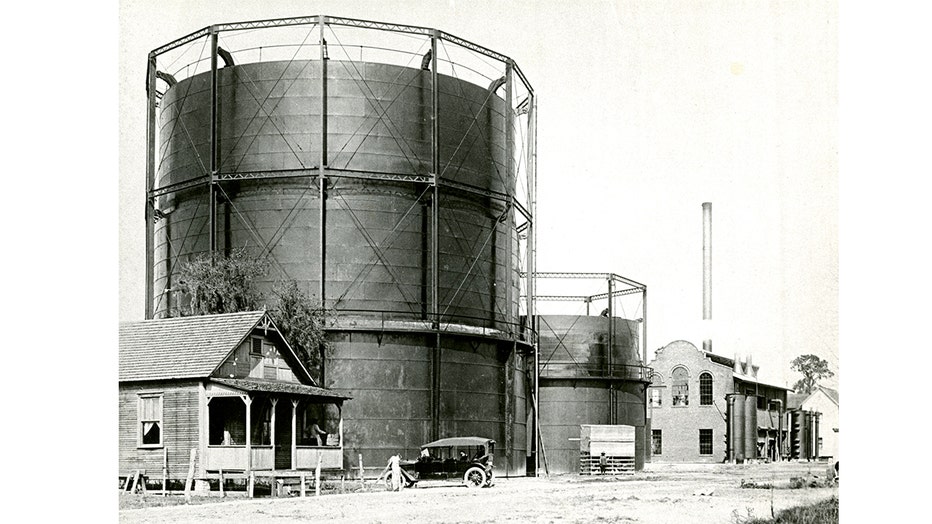

An aerial view of Gas Plant, where the two gas towers are visible. This is before the interstates were built.

Ultimately, St. Petersburg officials offered up the Gas Plant neighborhood, 66 acres located just north of Interstate 175 and east of Interstate 275. It was already designated for redevelopment. On at least two occasions, council members deemed the district as a "slum and blighted" area.

The original Gas Plant redevelopment plan was to create new housing options, commercial spaces, and an industrial park that would lead to 680 jobs, plus construction jobs over the following years. A referendum was held and the majority of St. Pete residents voted in favor.

MORE: Gas Plant District in St. Pete: One of the oldest Black neighborhoods razed for baseball

By 1983, city officials modified that plan and added a "multipurpose stadium" to the mix. A bond committee was formed to raise money to build the stadium. That was approved by the city council.

"This was evolving from different points. When we saw that the county and the city could work together, we had this development, this 66-acre site that was going to be vacant," Mussett explained. "It was very much near the interstate, which is really good for people coming from Tampa or Manatee County, the regional area. It was deemed a good opportunity. That site popped up because it was already available."

Two natural gas cylinders in the Gas Plant neighborhood. They were later demolished to make way for a multi-purpose stadium,. (Provided by the City of St. Pete)

When asked if another referendum was required to build a stadium, Mussett said, "We did not have to do it in that case." The land was already in the process of being acquired by the city and the plan was amended.

Demolition of the Gas Plant neighborhood began in 1984 and that's when the city came across a new issue: environmental contamination. The district was named after two natural gas towers, which ended up being the pollution source.

FOX 13 Archives: St. Pete dome controversies

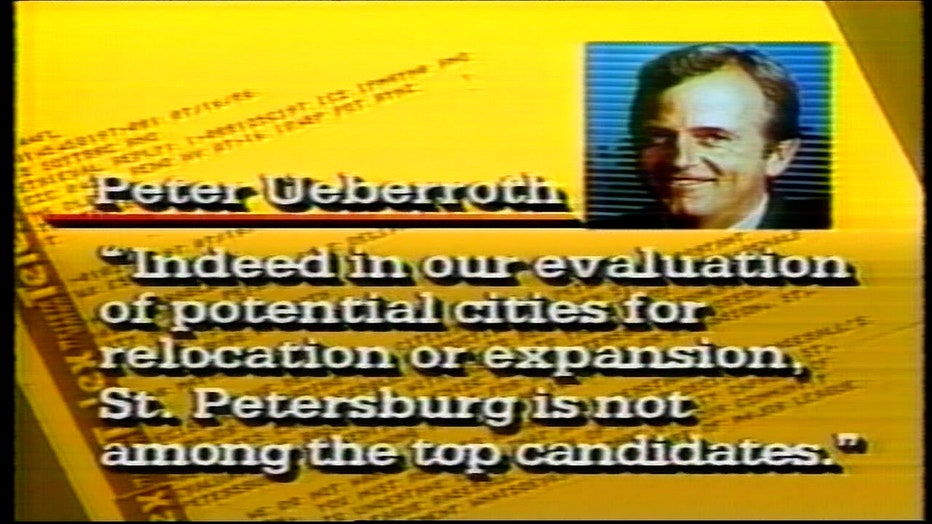

In the days, months, and years leading up to the St. Pete dome groundbreaking, it had its share of legal and financial controversies. Not everyone was on board, including Mayor Ed Cole. During this time, the MLB commissioner stated, ‘St. Petersburg is not among the top candidates' for a home team.

"One of the gas plants leaked. That had to be cleaned up. EPA had to approve it, to protect everything. It got removed, and they had to backfill with fresh dirt," Mussett explained. "Once, that got done, then they could start building. The gas plant owners had to take care of that [financially]."

As for the stadium design, the slanted dome shape was chosen for several reasons: the slope would reduce cooling costs, it would protect the stadium from Florida's thunderstorms and heat, and could better handle hurricane-force winds.

After construction and gas leak clean-up, the entire stadium cost $138 million, according to the MLB. St. Pete also acquired the 20-acre Laurel Park, a low-income housing complex, on the west side of 16th Street South. Those living there were relocated, and the buildings were demolished to make way for additional parking spaces.

FOX 13 Archives: St. Pete dome groundbreaking

On Nov. 22, 1986, it was groundbreaking day for the stadium dome, with the hopes of attracting an MLB team to St. Pete. Mickey Mouse and Goofy were even in attendance. Everyone from children to adults had their own shovel for the groundbreaking. Mayor Ed Cole, who was against the stadium, was not in attendance, but vice mayor Bill Bond was one of the speakers.

During construction, the city tried to lure the Chicago White Sox, and St. Pete almost became the new home for the team. The White Sox was going through its own stadium saga at the time.

In 1986, Peter Ueberroth, the baseball commissioner at the time, said in a telegram to Mayor Edward Cole Jr. It read in part, ''In our evaluation of potential cities for relocation or expansion, St. Petersburg is not among the top candidates."

"We almost had them here. I had one of my guys who was an architect in my department, and he started doing a design plan for how that could fit and work. It got very close, and we probably would have had them," Mussett said. "We asked the state to help fund building an updated stadium. Nobody wanted to step up and fund that. When the county couldn't get to first base, so to speak, that was it for the state."

Mussett and Rick Dodge, the assistant city administrator at the time, attended MLB meetings to build connections.

FOX 13 Archives: Early years of the St. Pete dome construction

In this report on January 5, 1987, Pulse 13's Marianne Pasha describes the status of the dome construction, which was put on a fast-track schedule with the goal of completing it in two years. At this point, there were unresolved lawsuits and questions surrounding the stadium's design.

"What Rick Dodge and I would do is we would go to find these guys in lobbies and try to tell them, ‘Hey we think St. Petersburg, the Tampa Bay Area, is a great place for a baseball team,’" he recalled. "We would meet with them, let them know we are out there. We became really good friends with the White Sox owners. They were helping us meet other owners because the owners are the ones that do all the important voting for future expansions."

Ultimately, the Illinois governor pushed for the state legislature to set aside funding to keep the team in Chicago. The new Comiskey Park opened in 1991.

FOX 13 Archives: Preparing for St. Pete dome’s opening day

Construction was in its final stages for the St. Pete dome as rehearsals were held for the grand opening. Kenny Rogers was slated to headline the gala, with organizers promising a ‘big bang of a show.’

The Florida Suncoast Dome finally opened Feb. 28, 1990 – without a baseball team. It wouldn't be until eight years later when the Tampa Bay Devil Rays held its first home opener.

Today, downtown St. Pete is no longer a sleepy strip like it used to be. It's a thriving area for both tourists and locals with plenty of shops, restaurants, and bars to choose from. It has museums, the annual St. Pete Pride parade, and St. Pete Pier.

FOX 13 Archives: Florida Suncoast Dome opens – finally

It was years in the making, but the Florida Suncoast Dome held its grand opening on March 3, 1990, with performances and thousands in attendance. FOX 13’s Kelly Craig was the host and Kenny Rogers was headlining the event. The city had yet to be awarded an MLB team.

Building Tampa Bay (Devil) Rays

Before their first home game, there were many tenants under the Florida Suncoast Dome over the years. There was arena football, concerts, tennis competitions, and the Tampa Bay Lightning. Between 1993 and 1996, the stadium was called Thunderdome.

St. Pete missed out in the 1993 MLB Expansion, but 1995 was their year. The Tampa Bay Devil Rays were coming.

In 1996, Rick Vaughn joined the team as vice president of communications and faced some hurdles as officials began crafting a team – both on the field and off the field.

The early construction days of the Florida Suncoast Dome (Provided by City of St. Petersburg)

Experience from the top

To start, he said the top positions in the organization, including the owner of the team "had never been in baseball before." Vaughn had spent almost a decade with the Baltimore Orioles.

"I was one of the few people on the business side of the organization, that had been in the game, that know a little bit, and had some institutional knowledge of how things work," he explained. "I think that was a real challenge for us, was not just educating the community about who we were, it was also educating our own people about what we needed to do. So I think right from the very beginning that was tough."

Building relationships with the community

When it came to creating a fan base, he said the organization had to communicate that it wasn't a St. Petersburg team that was coming, it was a regional team.

"When we first started in ‘96, the perception of, ‘Well, we’re in Tampa, and they're in St. Pete,'" Vaughn recalled. "I had people tell me, ‘Oh, that bridge across the bay might as well be 100 miles long.’ We worked really hard to not neglect St. Pete, but to be pretty active in Tampa and to let them know that we were the Bay Area's team."

He also said the area had more of a "football mentality" considering the Tampa Bay Buccaneers have been around for about two decades at this point. He said it was important to educate potential fans that there would be dozens of games throughout the season, not just one per week.

"One of the beauties of baseball that I always loved was the rhythm of the season. You know, in many ways it's like a soap opera. Every day, something happens," Vaughn said. "Trying to get people to be a bit more patient about things and not go crazy over every loss. So, it's just changing the mentality of people."

An outdated stadium

The Florida Suncoast Dome may have opened in 1990, but within six years, it was already considered to be outdated.

FOX 13 Archives: Preparing for St. Pete dome’s opening day

Construction was in its final stages for the St. Pete dome as rehearsals were held for the grand opening. Kenny Rogers was slated to headline the gala, with organizers promising a ‘big bang of a show.’

"I actually happened to be working in Baltimore as a PR director for the Orioles when Camden Yards was built in 1992," Vaughn explained, "And so that began this new wave of retro ballparks that were the way to go. Everybody copied that concept all around baseball and still really doing it. So, yes, I think it helped that we had a park. It showed a commitment. I just it was a shame that it got outdated really fast."

In October 1996, the Trop closed for 17 months, so the team could give it an $85 million facelift.

Beyond those hurdles, Vaughn said there was excitement thrown into the mix. After all, Tampa Bay will be calling this professional baseball team their own.

"Yes, there was a tremendous amount of excitement about it. I remember when we put our tickets on sale for the first time," he recalled. "You could get online and buy tickets, or you could come down to the Trop. And we had, basically, our whole roster there, out front, signing autographs, and the lines were blocks long."

A Tampa Bay Rays fan holds up a sign that reads, 'Hoo Rays for Tampa Bay' during the first home opener game on March 31, 1998. (FOX 13 / File)

In 1998, the ballpark was ready. Ahead of the first game, a "human chain" was built from City Hall to Tropicana Field. A baseball was passed along from one end to the other to promote the home opener.

"I was in the chain," Mussett said. "That's just how excited everybody was."

The Rays would go on to have two World Series appearances – but lose in both cases; the only stingray tank in an MLB stadium; some catwalk controversies and some of the lowest attendance rates in the MLB.

Rays touch tank at the Trop

A dedicated team from the Florida Aquarium takes care of the stingrays inside the touch tank at Tropicana Field.

MORE: Tropicana Field welcomes cownose stingrays in new touch experience

"I think we made some mistakes early on and part of that was because of a lack of experience, as I talked about before with some of our people in high-level positions," Vaughn explained. "We also didn't play very well. We finished last, nine times in our first ten years. It was difficult to go that long without winning. The Buccaneers kind of did the same kind of thing before they got it turned around, but it made it another challenge that we had to overcome."

The MLB has not had an expansion since 1995. The team is young, in fact, the youngest – along with their expansion brother, the Arizona Diamondbacks. With that said, there are signs of generational fan forming, Vaughn said, not to mention those who are die-hard and have been attending games since the very beginning.

Rays superfan has extraordinary way of spreading joy

Ellis is a big Tampa Bay Rays fan, and his parents surprised him at work with tickets to the World Series. While he might seem like an ordinary baseball fan, who gets joy out of the success of our local team, he has a way of impacting others through the joy he spreads.

The Tropicana Field lease ends in 2027. The Tampa Bay Rays' next steps are still in the works, but maybe, those lessons from the past will provide that little ray of sunshine on what to do in its future.

The historical information in this article was provided by Rick Vaugn, former VP of communications for the Tampa Bay Rays; National Baseball Hall of Fame; Preserve the Burg; and the Florida Grapefruit League.