Tampa’s Path to Equality Part 3: 'Election of the Century'

Black History Month: Tampa's path to equality

FOX 13 Chief Political Investigator Craig Patrick tells the story of Tampa's 48th mayor, Julian B. Lane, and his critical role in the Civil Rights Movement as one of the first southern mayors to support racial integration.

TAMPA, Fla. - Black History Month takes place in February to line up with the birthdays of Abraham Lincoln and the abolitionist Frederick Douglass. It also marks the anniversary of sit-ins that took off in February 1960 from North Carolina to Florida.

By 1960 in the city of Tampa, high school students like Arthenia Joyner were ready to take down segregation. They knew more about injustice than they ever cared to learn – after North Florida's Rosewood massacre of 1923, after a Lake County sheriff and his posse terrorized four men and killed two in the Groveland injustice of 1949, and after Harry T. Moore led the Florida NAACP, registered African Americans to vote and a blast of dynamite killed Moore and his wife on Christmas 1951.

Pictured: Harry T. Moore and his wife, Harriette.

"It's devastating. It's extremely painful," said USF Africana Studies and Anthropology Professor Dr. Cheryl Rodriguez. "And their crime was that they were struggling for equal rights for black people in Florida."

Tampa's Path to Equality Part 1: The First Steps

These are the catalysts of Tampa's awakening because it motivated students like Joyner.

"We are not going to step back and be trampled over," she said.

Pictured: Arthenia Joyner.

After Moore's murder in Brevard County, the leadership of the NAACP shifted to Tampa.

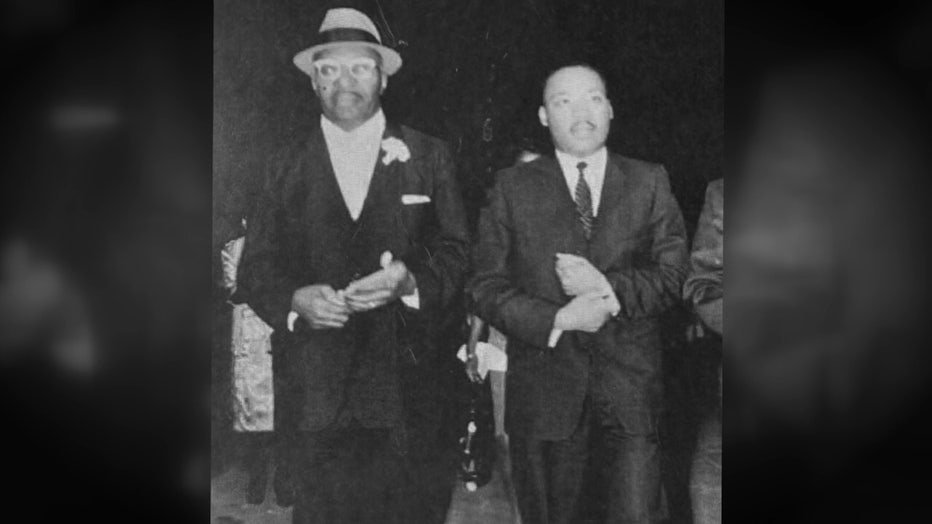

Middleton High School grad and Army veteran Robert Saunders took the reigns as state field director. As Dr. Martin Luther King formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Atlanta, Tampa Rev. A. Leon Lowry (King's former teacher at Morehouse College) became Florida's NAACP President.

"He was a newly arrived African American ministerial leader," said retired judge and oral historian E.J. Salcines. "He had not lived in Tampa. He was not a native of Tampa. So, he came with fresh new ideas, with perhaps a fresh new approach."

Pictured: Rev. A. Leon Lowry with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

So did Tampa's new mayor, Julian Lane, a dairy farmer and former UF football player. He defeated a well-known incumbent in the fall of 1959.

"It is one of the elections of the century," said USF Professor Emeritus Dr. Gary Mormino. "He's an all-American story. I mean, really, he goes to the University of Florida and is captain of the football team. I mean, does it get bigger than that in Florida for campaign credentials?"

He also served in World War II at Camp Livingston, which had a profound impact on him.

Pictured: Julian B. Lane, Tampa's 48th mayor.

"He ended up being lieutenant colonel and was in charge of the African American units," explained Mayor Lane’s grandson Julian Lane III. "He was sending soldiers that were committing their life to fight for the country and were dying on the battlefield but would come home and still be segregated. And he always believed in being fair and always believed in doing the right thing."

Tampa voters elected one of the first southern mayors to support racial integration, though they did not know that when they voted for him.

He didn't mention it on the campaign trail and people didn't think to ask.

Tampa's Path to Equality Part 2: The Awakening

"It was only about a six-week election cycle," said Julian Lane III.

As one of his first acts, Mayor Lane formed a biracial committee and picked Rev. Lowry and some of the city's most respected black and white community leaders to serve on it.

"Lane had the insight that a committee of people from the black and white communities—if they could talk, if they could communicate, they could solve issues before they exploded," said civil rights historian Dr. Steve Lawson.

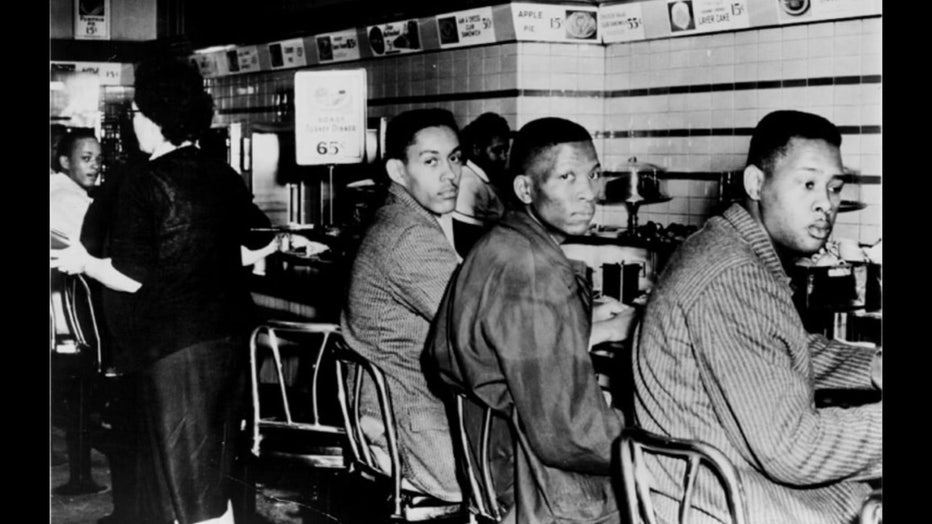

That led to the flashpoint of February 1960. Black students in Greensboro, North Carolina peacefully sat at segregated lunch counters. The sit-in movement rapidly spread south, white Supremacists lashed out at the integrationists, and with the new age of television, it played out in living rooms across the nation and activated students in Tampa.

Pictured: A sit-in at a segregated lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, in 1960.

"The almighty press let the world know what was going on. And people got energized and fired up and realized that we, too, are America," said Joyner.

Unlike the ugly scenes to our north, Tampa had a plan to protect the students and community leaders advising both sides.

"They knew it was coming, and they were able to guide it into a disciplined, nonviolent movement," Lawson said.

The Source: The information in this story was gathered by FOX 13 Chief Investigator Craig Patrick.

STAY CONNECTED WITH FOX 13 TAMPA:

- Download the FOX Local app for your smart TV

- Download FOX Local mobile app: Apple | Android

- Download the FOX 13 News app for breaking news alerts, latest headlines

- Download the SkyTower Radar app

- Sign up for FOX 13’s daily newsletter