Tampa’s Path to Equality Part 4: The Sit-ins

TAMPA, Fla. - One of the most remarkable and least known chapters in Black history took place in Tampa 65 years ago. Black and white community leaders helped integrate lunch counters long before the rest of the American South in a striking shift in race relations.

In 1955, Tampa's booming suburbs were restricted to whites. Black people lived separate lives and were banned from eating out with white people.

"For white Southerners, that was an intrusion. That was an invasion of social space that was forbidden," said civil rights historian Dr. Steve Lawson.

However, the power structure started to shift with the inauguration of Gov. LeRoy Collins in January 1955. He supported segregation on the campaign trail but connected with civil rights leaders as governor.

"He actually became involved with black leaders in Florida," noted USF Professor Dr. Cheryl Rodriguez.

Rodriguez' father, Francisco, was a Tampa lawyer who filed a blitz of lawsuits against Jim Crow laws, and yet Collins still took his calls.

Pictured left: Francisco Rodriguez.

Cheryl Rodriguez: "His wife answers the phone, they asked to speak to the governor, and he comes to the phone," said Dr. Rodriguez.

Before Christmas of 1959, the leaders of Tampa started doing the same thing. Mayor Julian Lane appointed black and white community leaders to a new board focused on bringing people together.

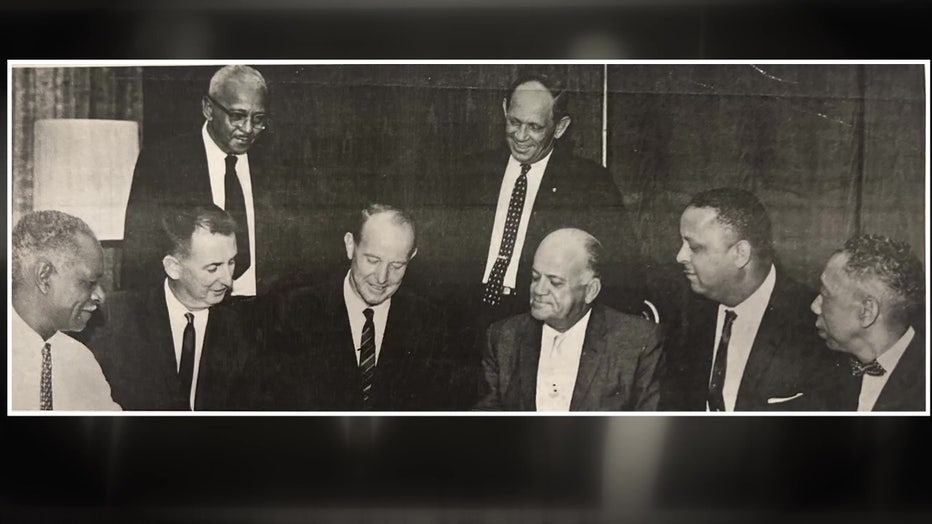

A biracial committee was appointed to a new board in Tampa focused on bringing people together.

"He created in ‘59 a biracial committee, even before there were any recent outbreaks here," said civil rights historian Dr. Steve Lawson.

READ: Tampa's Path to Equality Part 1: The First Steps

His picks included high-powered attorney Cody Fowler who led the American Bar Association, and Tampa Rev. A Leon Lowry, President of Florida's NAACP.

"It's about people getting together and being unified," said Rev. Lowry’s wife Shirley Lowry.

Lowry also had a right-hand who led the NAACP youth council—a young Tampa barber named Clarence Fort.

In February 1960, Fort watched the sit-ins in North Carolina and started planning similar protests in Tampa.

"I don’t think any of us really knew what we were getting into when we started that civil rights movement," said Fort. "I don’t know how I got so much nerve, but I just decided if others could do it, we could do it too."

He recruited around 40 students at Tampa's two black high schools, Blake and Middleton.

Jim Hargrett was one of the first students picked.

"I wasn’t really one of the outgoing people," said Hargrett. "I guess we weren’t as fearful as we should have been. We were just kind of excited to do it."

Arthenia Joyner was the last student picked.

READ: Tampa's Path to Equality Part 2: The Awakening

"He said I waited to select you last because you talk so much. The whole world would have known it before we even got there because I was known to be very loquacious," Joyner recalled.

Rev. Lowry and Francisco Rodriguez advised, trained and inspired the students.

"Yes. They were wonderful. Reverend Lowry, strong, well-respected gentlemen. And Francisco Rodriguez was this silver-tongued, brilliant lawyer that we knew that if it became necessary, he would get us out of all of it," said Joyner.

On February 29th, they gathered at historic St. Paul A.M.E. Church, walked to Woolworth on Franklin Street downtown, and sat at the lunch counter.

Students participate in a sit-in at Woolworth on Franklin St.

"I always took the first seat every time we had the sit-ins," recalled Fort.

"And we sat for a while. And then consequently, later we left because nobody, nobody made an effort to serve us at all," Joyner said.

"We just closed it down that day and went home," added Hargrett.

The next day the press described it as a faltering effort, but it was just the start.

"I remember them saying we won’t go, we won't go," Fort noted.

They returned through the first week of March, and Mayor Lane ordered police to protect the students.

"Some of them ride in the police cars to the lunch counters," said Mayor Lane’s grandson, Julian Lane III.

"Yes, they stood behind us," Fort said. "That's why we were so successful in Tampa, because they stood behind us, police officers, to make sure no one got to us."

This proceeded for four days, setting up the next act.

"When the biracial committee and the mayor agreed that if they could get the students to call off the demonstrations, then the biracial committee would negotiate with the merchants," Dr. Lawson said.

The students trusted the mayor and his committee and stood down.

"Now we're actually having a dialog," said USF Professor Emeritus Dr. Gary Mormino. "And that's a major breakthrough in civil rights in a southern state and a southern city."

Governor LeRoy Collins made the next move by opposing segregation and creating a statewide bi-racial committee modeled after Tampa. And negotiations in Tampa convinced stores to integrate their lunch counters.

A statewide bi-racial committee modeled after Tampa.

Craig Patrick explains how it all came together, and what we can learn from it in the next chapter of his series, Tampa’s Path to Equality.

CLICK HERE:>>> Follow FOX 13 on YouTube

The Source: Information for this story was gathered by FOX 13's Craig Patrick.

STAY CONNECTED WITH FOX 13 TAMPA:

- Download the FOX Local app for your smart TV

- Download FOX Local mobile app: Apple | Android

- Download the FOX 13 News app for breaking news alerts, latest headlines

- Download the SkyTower Radar app

- Sign up for FOX 13’s daily newsletter