USF opens exhibit on Black gravesites, Tampa Bay's African American history

TAMPA, Fla. - USF has unveiled a new exhibit designed to pull the veil off of dozens of unmarked cemeteries in Tampa Bay, a step Black leaders hailed as critical in cultivating a new approach to teaching the history of African Americans.

It's an approach that acknowledges the hardships they have experienced.

"I want to make sure that we do all we can to teach our history accurately and to make sure that we preserve it," said State Rep. Fentrice Driskell (D-Tampa).

The new exhibit is called "What Lies Beneath".

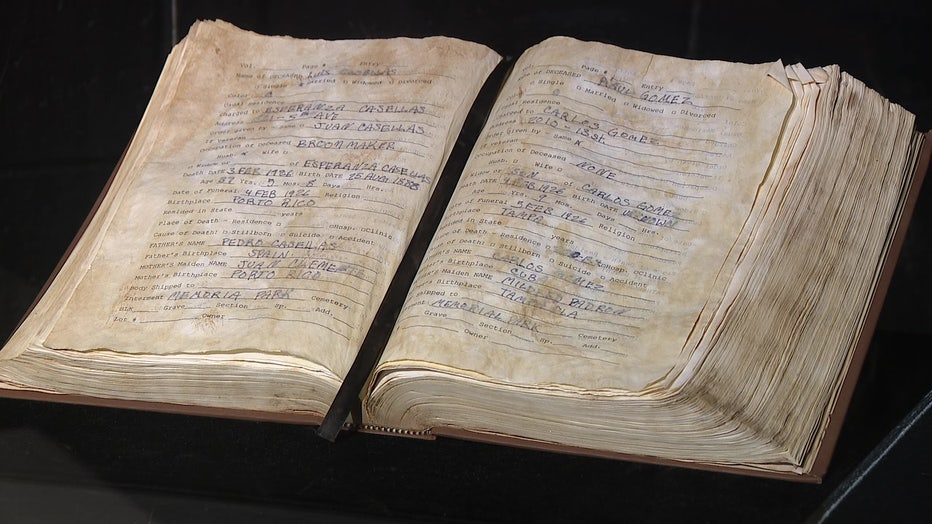

In a new exhibit called "What Lies Beneath" USF researchers are showcasing not just the location of 45 confirmed or suspected sites of unmarked cemeteries, with at least half of them Black, but the stories behind those buried.

Some cemeteries were covered by housing, others by private development, and still others were buried, with grass allowed to grow on top until only sonar could pinpoint their location.

READ: Tampa's first-ever cemetery coordinator helps preserve historic cemeteries now owned by the city

"What I tell young people is history is not just studying things that happened in the past," explained Fred Hearns of the Tampa Bay History Center. "It's a gateway to the future, because the better we understand our history, the better prepared we are to move forward."

USF is taking a new approach to teaching the history of African Americans in Tampa Bay.

Public officials in Tampa Bay began focusing on unmarked graves in 2019, when researchers found 120 Black grave sites in Robles Park, likely covered over as segregation flourished in Florida in the 1950s.

Christina Arenas believes her family, some of whom were enslaved, and many of whom were victims of segregation, are among the fifty buried at a forgotten cemetery in Citrus Park.

USF is taking a unique approach to Tampa Bay history.

"Our ancestors will not be forgotten," she said. "We will continue to speak their names."

The USF study was spurred by county commissioners, while the state has set aside $1 million to study more of them.

They have found fifteen of the 45 sites were classified as white during segregation, and 13 were not classified by color.

"It's really kind of the beginning in the sense that there's so much research still to do, and we hope to find other ways to share that," said exhibit curator Erin Kimmerle.