USF researchers study effectiveness of quarantines using remains from Black Death plague

TAMPA, Fla. - In a first-time study, University of South Florida researchers are looking into the effectiveness of pandemic quarantines. And, they're using skeletons as old as 600 years from Venice, Italy, to study people who died from the Black Death plague and other diseases.

"We can do that simply, because we can look at how many people died in the old Lazaretto. That is the first quarantine at 1423," said Andrea Vianello, a visiting research fellow with the department of anthropology at USF. "And then we can look at basically what killed them, and we can compare with the historical records and see if that is more or less recorded there in the genetic evidence and the scientific record. From that we can say, if it is more obviously the quarantine worked, and we can say it stopped some pathogen, some epidemics."

Vianello said he along with USF’s Robert Tykot and Rays Jiang are looking at genetic response to the diseases, the changes that happened to humans and the virus with the public health countermeasures, and testing the effectiveness of those pandemic quarantine measures.

"So it's the first time that we can test really the lock downs and the masks if they worked really," said Vianello. "Well, in the past, we assumed essentially that all these countermeasures, lock downs and the quarantine and masks, they all worked, that that is what the historical sources tell us. We never really tested them scientifically."

The Venetian government is allowing the researchers to study hundreds of remains of people who died from the Black Death plague and other diseases over a 300-year period.

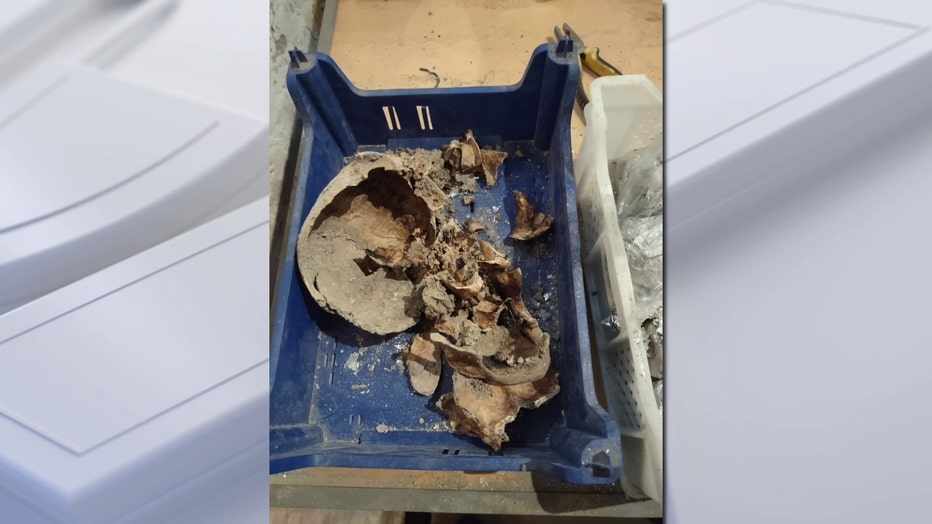

"I actually saw where all the crates and boxes where more than a thousand people, their bones were in these and actually held them in my hands as we went and took samples of the teeth and bones for the kinds of analysis that we would be doing," said Robert Tykot, an anthropology professor at USF.

Those people were quarantined on a man-made island known as Lazzaretto Vecchio or Old Lazzaretto, the site of the world’s first isolation hospital. Sick people who died were buried on the island from the 1400s to the 1700s, Vianello said. The ancient DNA samples will come to Tampa, USF genomics professor Rays Jiang will use machines to find the different diseases, the changes in them, and where they came from.

"Why sometimes success and sometimes failure? Is it the pathogen, is it the human or is it the public health control like quarantine and this is the first time we have the ability to put all the information together," Rays Jiang, an associate professor of genomics at USF Health.

The analysis will take a few years, but their hope is to better prepare the world for the next pandemic.

"We really needed to provide to people advice that is strong, that is scientific, scientifically rooted and sound, and then people can make their own choices, but based on science and not on opinions, whether they are from physicians or from anybody else," said Vianello.

The researchers said the remains come from a time in history that is important due to the global trade happening in the 15th century. They said this kind of study would not be possible with COVID-19 because the virus is rapidly changing and people travel much more frequently than they did hundreds of years ago.

"We started working on this before COVID came around. We started doing this back in 2018, 2019, where we got the permission to go and work on these remains. We were actually going to go and get them in the spring of 2020 when COVID came around," said Tykot. "So this was not a response at all, but we were already thinking about this kind of thing with the spread of diseases just in general."

Once the project is finished, it will be shared with the public on a permanent display in a museum in Italy.