Willie Mays' legacy lives on in St. Pete: 'The fans loved him and he loved them back'

ST. PETERSBURG, Fla. - The days of his explosive swing, his riveting speed and his one-of-a-kind glove were mostly memories by the time Willie Mays came to play in St. Pete, but his smile and aura were with him until the end.

"He was a fan favorite, there's no two ways about it," said baseball author Peter Golenbock. "The fans loved him, and he loved them back."

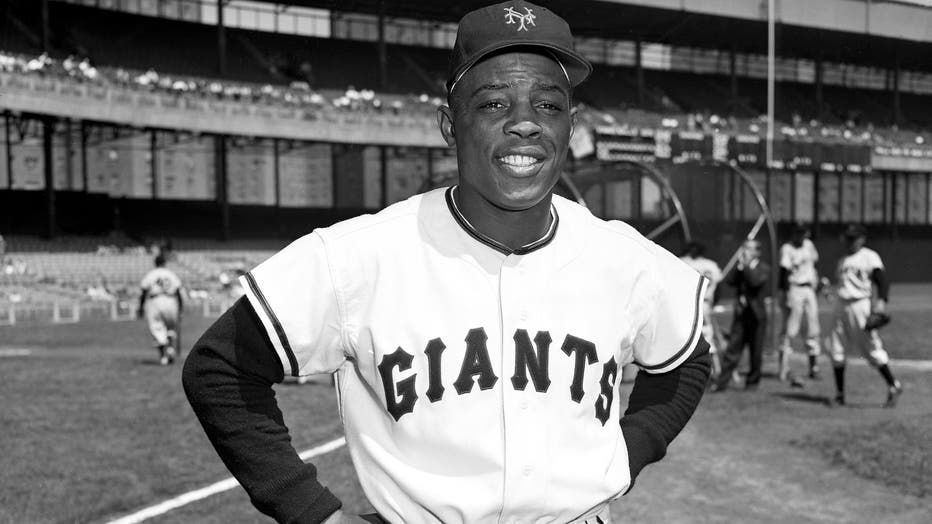

Baseball fans of the ‘50s and ’60s, like Golenbock, remember Mays mostly as a New York and San Francisco Giant.

New York Giants Willie Mays No. 24(Photo By: Walter Kelleher/NY Daily News via Getty Images)

He racked up 660 home runs, nearly 3,300 hits, 12 Gold Gloves and solidified baseball as our national pastime, after decades of the game excluding players like him.

"They say about (Babe) Ruth when you went to the stadium to see Ruth, you were looking to see whether he'd hit a home run," said Golenbock. "You go to the stadium to see Willie Mays and you're looking for everything."

Mays died on Tuesday, just two days before a game was to be hosted at Rickwood Field in Alabama between his Giants and the St. Louis Cardinals.

RELATED: MLB icon Willie Mays dies at 93

He had played there in 1948 for the Birmingham Black Barons.

"When he called in to say that he wouldn't be able to make it, that he would watch it on television, I knew for him the end was near," said Golenbock.

Willie Mays only played in one Spring Training at Al Lang Stadium, hitting three homers in 13 at-bats, according to the book "100 Years of Baseball on St. Petersburg's Waterfront" by Rick Vaughn.

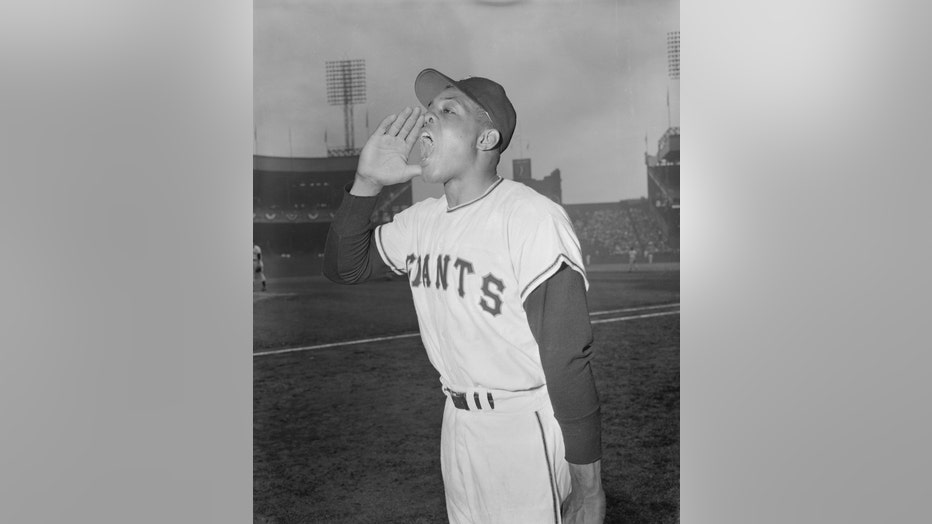

(Original Caption) Willie Mays of the Giants bellows his war cry of "Say Hey" here before the second game of the 1954 World Series got underway.

But his legacy lives on elsewhere in St Pete.

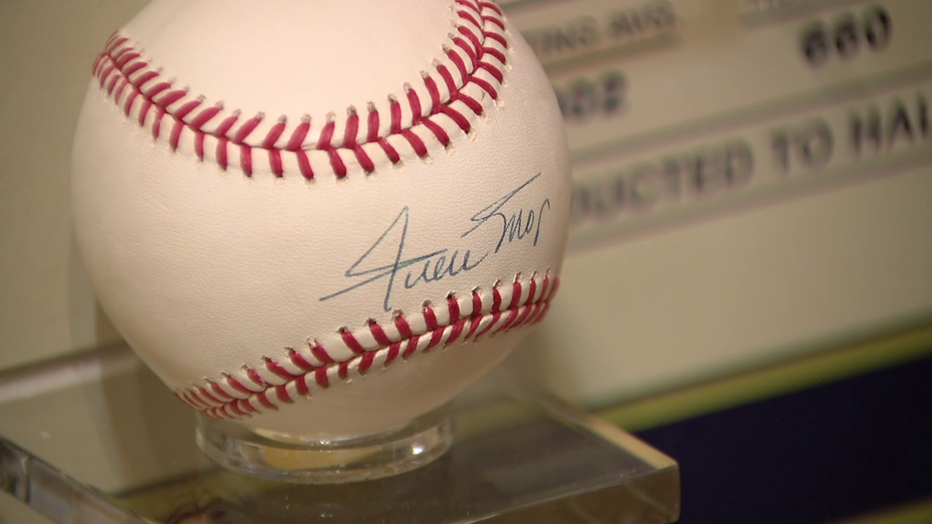

The St. Pete Museum of History has 5,000 signed baseballs, including three by the Say Hey Kid.

"When you look at everything and he actually signed this, this ball and he was here in town and it's just, it's just amazing," said Rui Farias, the executive director of the museum.

A signature shows the steadiness of someone's hand. In this case, it's of someone who was born to a working-class family in segregated Alabama, who used baseball to achieve universal respect.

"Baseball is a religion," Golenbock said. "He was a god."

SIGN UP: Click here to sign up for the FOX 13 daily newsletter